Dear Friends,

I’ve been thinking about practice over the past few weeks, how practice can be like a keel, how it helps you make deep contact with yourself. I’m also curious about the way in which practices communicate with each other, becoming expressive, becoming a way that we can make deep contact with each other.

In this talk I tell some stories about the artist Allan Kaprow and what he did in the years after he invented Happenings. For Kaprow, the practice of art became inseparable from the practice of life: ordinary, intimate, sometimes ridiculous, just like the practice of Zen.

— Sal (aka Kenzen)

Video & Audio: Brushing Teeth, Trading Dirt

Video and podcast audio here.

Transcript: Brushing Teeth, Trading Dirt

[This transcript has been lightly edited.]

Practice and Expressive Practice

This year I’ve been leading the Village Zendo’s Path class, along with Seiryū (writer Marco Wilkinson). The theme is practice, and more specifically, writing as a form of expressive practice.

Our work has excited my thinking about practice—in particular, about expressive practice. Expressive practice is a phrase we often hear at the zendo, but it's actually not widely used, so I’ll be exploring it today.

Practice is Doing

Practice is a word whose roots are in terms for doing. So practice a kind of an action. Even that small idea is interesting for me: Practice is not something that happens to us, it's something we do.

The way we might say in practice versus in theory. Practice is a doing word.

The ways in which we use the word practice also have an element of repetition. Practice is not just something we do, it's something we do again and again.

If practice is doing the same thing over and over, why is that repetition interesting? Why is that important, why does it do anything?

Practice is Noticing What Changes.

Repetition has many uses, but I'm not going to talk about rehearsal and those senses of the word practice.

In the kind of practice that we're thinking about, when you do the same thing over and over again, I think the first thing you really notice is that it's never the same. You are always different, and the whole world is always different, and those two things are not separate.

So, by fixing the doing or the action in one place, you immediately reveal to yourself the great constantly changing nature of reality.

Dogen put it this way, “when you study the Buddha way, you study the self.” One of the things he might have been talking about is that in Zazen (meditation), which is our most central study of the Buddha way, our most central practice, our complete selves are revealed to us—whether we like it or not, constantly, constantly revealed to us.

He goes on to say, “when you study the self, you forget the self.”

I think this speaks to the way in which that experience of our full reality tends to dissolve the barriers between what we conceptually think of as “the self” and the whole world selfing through us. Maybe we stop needing to hold on to this concept of “the self” so much.

“When you forget the self, you are actualized in all the myriad things.” You are actualized in the whole world.

The Practice of Meditation

So, Zazen is at the very heart of our practice. I teach beginning instruction; we can teach Zazen in an hour. It's not very complicated. It's actually extremely simple.

I think that act of sitting quietly, which is so simple, is common to many different spiritual traditions and other kinds of cultural traditions throughout human history. It appears in many times and places; it’s a fundamentally human thing to do: to just sit down and shut your mouth for a while and see what your experience is.

Practice of the Cook

One of the kinds of practice which we collectively explored over the winter—during our ango (intensive practice period)—is the practice of the tenzo (monastery cook).

Our study text was Dogen’s “Instructions for the Cook.” In that essay, written in 1237, Dogen writes about the practice of cooking for the monastic community. He talks very literally about what the tenzo does, and the attitude that the tenzo brings.

Here we see a form of Zen practice beyond meditation, which is cooking for the community. Dogen describes the cook’s tasks in great detail, and he talks about three minds, three kinds of attitude that are good to bring to being a tenzo, or to whatever work you do.

One is daishin, this is a vast mind or magnanimous mind; this is the mind of all that is. One is roshin, parental mind or nurturing mind, and the other mind he talks about is kishin, joyful mind, which is basically doing your work gladly and with gratitude.

All of these deepen the tenzo's activities as a form of practice. And this shows how we can see our lives, our whole lives in a similar way.

Allan Kaprow

I wanted to talk today a little bit about the artist Allan Kaprow.

He's best known for his work in the 60s as the inventor of happenings. Happenings were originally kind of a mix of performance, of participation, and of environments. They were a new art form that exploded what the idea of art was in its time.

It was the 60s, and the word “happenings” took off and became very popular. It caught the imagination, a many different kinds of people started to do many different kinds of happenings.

Kaprow became famous, and yet he came to feel that the mythology of happenings was parting ways with the reality that he had wanted to explore. So he stepped back into a much, much simpler, quieter practice.

He taught at Rutgers and then in the University of California system, and he mostly worked with his students or did projects with his friends, very often with no audience at all. He would write a simple set of scripts or instructions for his friends or his students to carry out and experience these small actions or interactions.

Brushing Teeth

I’m going to share one of his writings that bears on this idea of practice. This is from an essay called “Art Which Can't Be Art,” which he wrote in 1986.

It’s fairly well known that for the last thirty years my main work as an artist has been located in activities and contexts that don’t suggest art in any way. Brushing my teeth, for example, in the morning when I’m barely awake; watching in the mirror the rhythm of my elbow moving up and down . . .

He goes on to say that there was a move that artists made repeatedly over the last few decades, from the 50s through the 80s: they would take non-art things and put them in an art context—a gallery, a museum, on stage. This move came in part from Marcel Duchamp. Think of Duchamp taking an urinal and placing it in an art exhibition; it changes the way that you see that urinal, or any urinal, and it changes the art exhibition and the idea of what art is.

Artists kept making that kind of move but for Kaprow, it was no longer a satisfying or interesting move to make. He thought of it as aestheticizing real life, and he was actually interested in life itself.

To go on making this kind of move in art seemed to me unproductive.

Instead, I decided to pay attention to brushing my teeth, to watch my elbow moving. I would be alone in my bathroom, without art spectators. There would be no gallery, no critic to judge, no publicity. This was the crucial shift that removed the performance of everyday life from all but the memory of art. I could, of course, have said to myself, “Now I’m making art!!” But in actual practice, I didn’t think much about it.

My awareness and thoughts were of another kind. I began to pay attention to how much this act of brushing my teeth had become routinized, nonconscious behavior, compared with my first efforts to do it as a child. I began to suspect that 99 percent of my daily life was just as routinized and unnoticed; that my mind was always somewhere else; and that the thousand signals my body was sending me each minute were ignored. I guessed also that most people were like me in this respect.

He was making brushing his teeth a practice; kind of an art practice, but also not.

I think his experience of paying a new kind of attention to brushing his teeth points to another aspect of practice. It's not merely doing something, it's not merely doing something repeatedly over and over again. It's also doing something with your full attention, with your full self. I think, for me, very importantly, with curiosity.

Allan Kaprow and Zen

So it turns out—I hadn't known this—that Allan Kaprow was actually a Zen student. I found this out as I was working on the talk.

I wasn’t surprised that Kaprow had some kind of Zen influence. He was in the famous class on experimental music which the composer John Cage taught at the New School in 1957. The people in that class created an enormous explosion of new art forms. John Cage himself was influenced by Zen through the talks of D.T. Suzuki and he brought some of that new perspective to the class. And maybe Alan Kaprow had seen some of those talks at that time—he was certainly in an art milieu where Zen was part of the conversation in New York.

Either way, when he moved to San Diego in 1978 to teach, he became a student of Charlotte Joko Beck at the San Diego Zen Center.

There's a funny story about one of the things that happened there which I’ll share with you. The story also says something about the style or quality of his practice.

Heavy-Duty Buddhist Dirt

As I mentioned, he carried out these small interactions as his art practice. When he was living in San Diego, he had a house with a garden. As gardeners do, he cultivated his soil to make it rich and beautiful and productive.

One day he had the idea to take a bucket of soil from his garden, put it in his pickup truck, and find some other place of soil to trade it with, to trade his bucket for that place's bucket, and then keep going, trading bucket for bucket, and that was going to be the work.

Apparently he went to the Zen Center on Wednesdays. One Wednesday, he goes to the Center, and he sees a friend who's living there, whose name is Ben Thorsen. And he says, “Can I exchange my bucket of dirt for a bucket of dirt from here?” And Ben Thorsen says, “okay,” as one would.

Here’s Kaprow’s story about what happened next.

I went to get the bucket of dirt and shovel. When I came back Ben said, “I've got a better idea. Let's crawl under the Zen Center and get the dirt from just below the seat of our teacher” [Charlotte Joko Beck]. “That'll be heavy-duty Buddhist dirt!” I agreed it was a very good idea. We got a flashlight and squeezed our way under the floor of the house, dragging the bucket and shovel behind us. It was cramped, with maybe 15 inches of clearance, filthy dirty, cobwebs everywhere. But we couldn't determine the exact spot we were looking for. So Ben said he would go back out and would tap on the floor above; I could move over to where his taps were coming from, and tap back to him. That's what we did. At the right place under the floor, I scooped out a hole in the dreadful dirt that was only construction remnants. Replacing it with my garden dirt would be an improvement, I thought uncharitably. In any case, the heavy-duty Buddhist vibes were the main consideration. So I wiggled out with the stuff and brushed off my clothes.

Ben was thoroughly amused by then and said, “What are you doing this for?” I said, “Oh, it's what I like to do. No big deal.” He said, “Well, I guess it's no sillier than sitting on a cushion for hours doing nothing” (as we seem to do at the Center). We talked for some time about the meaning of life.

Then he goes on, a few weeks later, he's at a garden nursery and he is, oh, this is a good place. I'll do another exchange here. He asks the woman who's running the nursery, and she says yes.

He tells her this story of where the dirt came from, of this heavy duty Buddhist dirt. He says,

She was clearly impressed with the Buddhist part. '“I thought you were an artist.” I said to her yes and that this was what I did. “I thought you were a college professor.” “Sure. I teach this sort of thing, trading dirt.” “They pay you for it?” she asked me. Then she thought a moment. “But it's not serious; it's what my grandson does.” She gestured toward the child playing on the floor with cornhusks. “What's serious?” I said to her.

So we had a long talk about the meaning of life while I dug a hole at the side of the road. As I was about to pour the Buddhist dirt into it, she tossed some dry seeds into the bucket. I said “What did you do that for?” “Why not? It can't hurt,” she said.

All of these were encounters of trading dirt, but also conversations about the meaning of life and about the meaning of these kinds of actions. Kaprow went on and did this for about three years until he no longer lived in a place that had a garden.

Expressive Practice

I want to close by talking a bit about expressive practice. What is expressive practice? What's the difference between all the kinds of practices that we're talking about, and specifically expressive practice? What could that mean?

In part just means being with other people. We may think think of zazen as our own personal, individual practice, but when you do it in a group, you can feel the expressiveness of the zazen of everyone around you, the expression of their sitting. It has a powerful effect, at least for me.

Another form of expressive practice that we have as part of the Zen tradition happens in the interview room during daisan (conversation with a teacher). In daisan you meet face-to-face with a teacher, typically in a small room (or a Zoom room), and you express something; you ask a question or offer an expression of your understanding in some way. That expression makes possible the response of the teacher and begins a kind of mutual dialogue or conversation. This exchange of expressions is where the real teaching in Zen takes place.

Zen doesn't really take place in what we're doing right now, me speaking and you listening. Instead, it takes place in that intimate encounter with a teacher. That intimate encounter requires you, the student, to express something. If you can't express anything, nothing happens. So daisan, is a place where you practice expression regularly.

Expressive Arts

We also think of expressive practice as being all of the arts. We're very lucky to have poems written by members of the sangha of the Buddha in India at that time, expressing their understanding, expressing their life experience. They're very powerful poems.

You can see all of the arts in, and expressive arts in China and Japan, many of which are infused with Buddhist teachings.Calligraphy, poetry, painting, all of those become one thing in China. In Japan, many craft movements become infused with the Buddhist teachings, with Zen understandings, for instance ceramics. So we have so much expression from the past. Further, all of the texts that we read are in some sense, expressive arts.

These expressions communicate something to us, and they communicate not just by their content, whatever that might be, but by their manner, by their way, by their form of mind, in ways that can't fully be accounted for.

Expression of the Cook

And then there's the tenzo, to come back to the tenzo again. There's the tenzo attending to his own practice with this magnanimous mind, this nurturing mind, this joyful mind carefully cooking in the kitchen.

Once the food reaches the sangha, it's suddenly an expressive practice.

I think any of us who've had an experience of being on retreat with a tenzo or having a tenzo at zazenkai (one-day retreat), you know that when you receive the food, you are receiving the expression of that person in a very material and yet also, we might say, spiritual, kind of way. That is a reminder, therefore, that all of our work that involves other people has the potential to be a kind of expressive practice.

Our Daily Work

Many of us cook for other people daily. We also have artists in our sangha who are making music, painting, writing and other kinds of artistic expression.

We could also think of playing with a child as a kind of expressive practice, teaching in a classroom as a kind of expressive practice, being with somebody in the role of a chaplain as a kind of expressive practice, therapy with someone as a kind of expressive practice, managing a team, maybe even making a spreadsheet or writing some code. We can look at all of our lives and see our work in this kind of light, to look for places of practice in your life and places of expressive practice in your life.

Every day we offer this dedication at our morning work service: May our daily work be a source of practice, awareness, and compassion. This is an encouragement to think of your daily life and daily work as an expression of the Dharma, an expression of your full self.

Reality Expressing

I'll close by sharing a few more words of Allan Kaprow's, where he talks about the breath.

This is from the essay called “Performing Life,” written in 1979, shortly after he started Zen practice. He says:

Today, in 1979, I'm paying attention to breathing. I've held my breath for years—held it for dear life. And I might have suffocated if (in spite of myself) I hadn't had to let go of it periodically. Was it mine, after all? Letting it go, did I lose it? Was (is) exhaling simply a stream of speeded up molecules squirting out of my nose?

And he talks about some different kinds of breathing with others that he's experienced in his life. And then he goes on,

There's also the breathing of big pines in the wind you could mistake for waves breaking on a beach. Or city gusts slamming into alleyways. Or the sucking hiss of empty water pipes, the taps opened after winter. What is it that breathes? Lungs? The metaphysical me? A crowd at a ball game? The ground giving out smells in spring? Coal gas in the mines?

It's kind of funny to me that he ends with this less romantic, darker part of reality, but I think he's in the state of feeling that all of reality is always breathing, and all of reality is always practicing, and all of reality is always expressing.

What are some of your expressive practices? I’d love to hear from you.

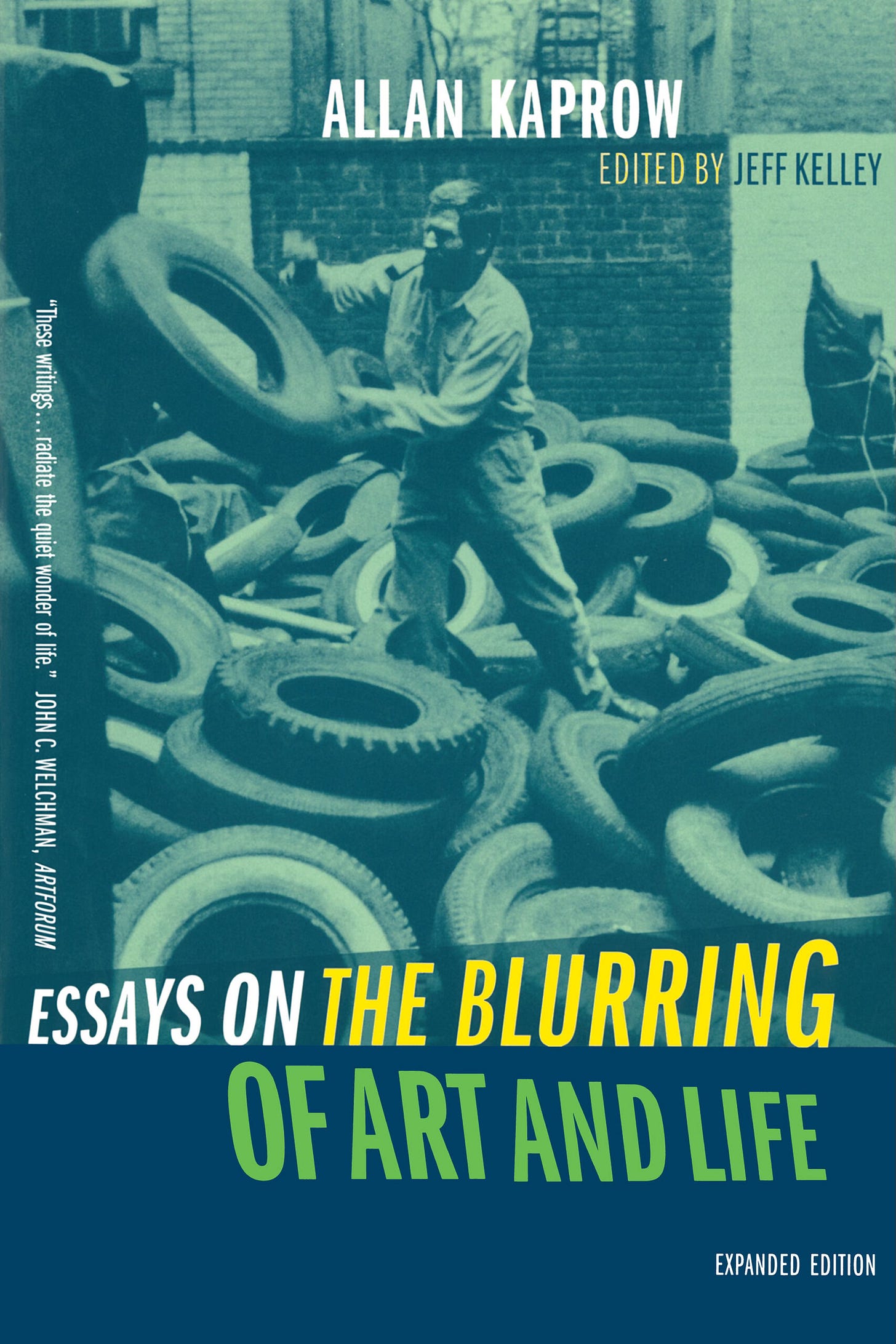

Allan Kaprow

Many of Allan Kaprow’s essays are collected in the book Essays on the Blurring of Art and Life, edited by Jeff Kelley, available from University of California Press.

The story about trading dirt is from Kaprow’s essay “Just Doing,” published in TDR, Volume 41, No. 3 (Autumn, 1997.).

Related Posts

Further adventures and new ways of seeing can be found in my book, The Uses of Art.

Artist Sal Randolph’s THE USES OF ART is a memoir of transformative encounters with works of art, inviting readers into new methods of looking that are both liberating and emboldening.

Dazzlingly original, ferociously intelligent.

— Michael Cunningham

A joyful, dazzling treasure-box of a book.

— Bonnie Friedman

Here’s a guide, to waking up, over and over again.

— Roshi Pat Enkyo O’Hara

Hey Sal, this is not the first time you've talked here about a book that's on my shelf, too, and now, looking at my copy of "The Blurring of Art and Life" I must admit it looks unread, which is odd, as I've always felt that Allan Kaprow meant something to me, not least his take on toothbrushing. So now I know what to read next, which is a treat (like discovering a band you love very late, by which time they've released many amazing albums, which is what happened to me with The Feelies).

Another thing that was great about this was that I first read your lightly edited version, and then, some days later, watched the film, which includes the edited out part about Mothers' Day, which I enjoyed. (It also contains the part about your brief aphonia, so here's hoping you've made a full recovery in the meantime.)

And finally, the part where you speak about expressive practice and the way it isn't actually Zen if it's just a one-way street, felt, in this filmed version where I can see you, Sal, actually telling me this directly, like a strong appeal to use this comments function as part of the experience of partaking of your talk. Yes! N.

This is great! I especially love the story of the heavy-duty Buddhist dirt : )