Dear Friends,

In this season of darkness and illumination we have a chance to reflect on our lives, and set intentions for the coming year. Today I’m heading up the Hudson to the Village Zendo’s annual winter retreat for a week of silence.

Our group will be collectively reading a 13th century essay by Eihei Dogen, one of the founders of Soho Zen in Japan. As a young monk Dogen traveled from Japan to Song Dynasty China in search of answers to his biggest spiritual question: if we already have a Buddha nature, an enlightened self, why is it that we practice?

What he found in China was not just his heart teacher, but a form of living where every action, every task was an expression of the way. He was especially struck by encounters with monastery cooks, tenzos, who treated each grain of rice and each mushroom as if it were the whole world of living beings.

The tenzos cooked for their communities while cultivating a joyful, nurturing, and magnanimous mind. When Dogen asked one of these cooks, an elderly, senior monk, why he didn’t let other people do the hard work, the tenzo said simply, “Other people are not me.”

Bringing this distinctive flavor of practice back to Japan, Dogen eventually established his own monasteries. To emphasize the importance of tenzos, he wrote “Instructions for the Cook” (“Tenzo Kyôkun”) which links the act of cooking for the community with the deepest aspects of Buddhist practice and aspiration.

What if we took this way of approaching cooking, or any other daily task, as a form of attention? This week’s Ways of Seeing explores the way of the cook, the tenzo: a joyful, nurturing, and magnanimous attention to all things.

& for those who have joined us recently, welcome! “Ways of Seeing” is a series of inspirations and practical exercises for deepening attention and engaging with art and the world. Let me know your own experience in the comments.

— Sal

PS: I’ll be taking the next two weeks off, one for the silent retreat, and one after for the new year. I’m pausing paid subscriptions (thank you, oh most generous ones!) and will be back January 16.

PPS: If you are feeling for cooking, check out who writes wonderful essays (with recipes!) in her substack Poor Man’s Feast.

UPDATE: Comments are fixed and now open—I’d love to hear from you.

Instructions for the Cook (Tenzo kyôkun)

When you prepare food, never view the ingredients from some commonly held perspective, nor think about them only with your emotions. Maintain an attitude that tries to build great temples from ordinary greens, that expounds the buddhadharma through the most trivial activity. When making a soup with ordinary greens, do not be carried away by feelings of dislike towards them nor regard them lightly; neither jump for joy simply because you have been given ingredients of superior quality to make a special dish. By the same token that you do not indulge in a meal because of its particularly good taste, there is no reason to feel an aversion towards an ordinary one. Do not be negligent and careless just because the materials seem plain, and hesitate to work more diligently with materials of superior quality. Your attitude towards things should not be contingent upon their quality. A person who is influenced by the quality of a thing, or who changes his speech or manner according to the appearance or position of the people he meets, is not a man working in the Way.

…

A dish is not necessarily superior because you have prepared it with choice ingredients, nor is a soup inferior because you have made it with ordinary greens. When handling and selecting greens, do so wholeheartedly, with a pure mind, and without trying to evaluate their quality, in the same way in which you would prepare a splendid feast. The many rivers which flow into the ocean become the one taste of the ocean; when they flow into the pure ocean of the dharma there are no such distinctions as delicacies or plain food, there is just one taste, and it is the buddhadharma, the world itself as it is. In cultivating the germ of aspiration to live out the Way, as well as in practicing the dharma, delicious and ordinary tastes are the same and not two. There is an old saying, “The mouth of a monk is like an oven.” Remember this well.

…

Likewise, understand that a simple green has the power to become the practice of the Buddha, quite adequately nurturing the desire to live out the Way. Never feel aversion toward plain ingredients. As a teacher of men and of heavenly beings, make the best use of whatever greens you have.

…

Magnanimous mind is like a mountain, stable and impartial. Exemplifying the ocean, it is tolerant and views everything from the broadest perspective. Having a Magnanimous Mind means being without prejudice and refusing to take sides. When carrying something that weighs an ounce, do not think of it as light, and likewise, when you have to carry fifty pounds, do not think of it as heavy. Do not get carried away by the sounds of spring, nor become heavy-hearted upon seeing the colors of fall. View the changes of the seasons as a whole, and weigh the relativeness of light and heavy from a broad perspective. It is then that you should write, understand, and study the character for magnanimous.

…

From Eihei Dogen, “Instructions to the Cook” (Tenzo kyôkun), translated by Thomas Wright, included in How to Cook Your Life: From the Zen Kitchen to Enlightenment.

Exercise: The Cook

Choose a work of art or an “object made to be seen” to offer your attention.

Begin by simply observing. Ask yourself, “what are the ingredients here?” Let go of judgment about whether these ingredients are good or bad, plain or fancy. Discover what sort of meal can be made from these ingredients.

Second, see what is before you as a meal that has been cooked for you. Experience it fully. Enjoy it! Ask yourself what ways this meal can nourish you.

Finally, let yourself expand into the magnanimous mind. Let yourself take in every part of your own experience, every part of your own life.

Afterwards, give yourself some time to take notes. Consider sharing your experience in the comments here.

As with all of these “Ways of Seeing,” the initiating impulse is to expand our possibilities for engaging with works of art and deepening attention to everything around us. These exercises are perfect for time spent in museums, galleries, and studios. You can also bring them into the rest of your life and experiment with streets, libraries, parties, landscapes. Try them as writing or art-making prompts.

These practices work best if you give them some time.

As ever, interpret these instructions freely and intuitively. Make them your own.

How to Cook Your Life

How to Cook Your Life: From the Zen Kitchen to Enlightenment includes a translation of Dogen’s Tenzo kyôkun (Instructions for the Cook) and a commentary by Kōshō Uchiyama Rōshi. It is available from Shambhala Publications.

If you need to read it right away, a PDF can be found on Terebess.

Instructions to the Cook

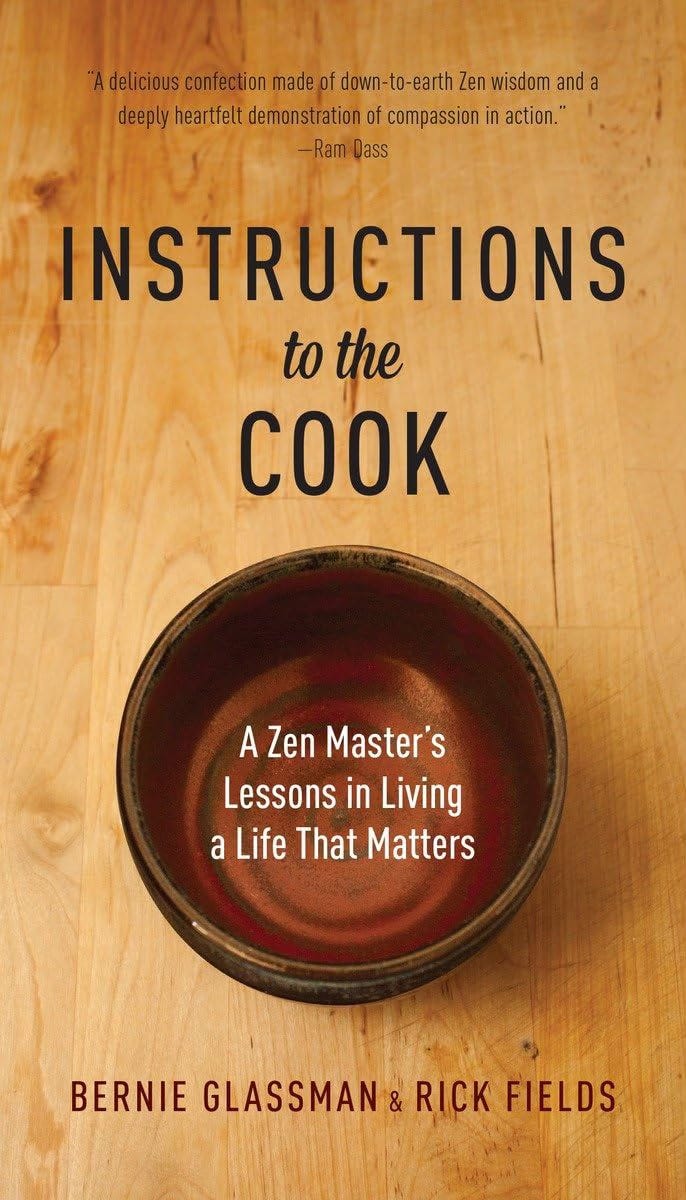

Bernie Glassman and Rick Field’s Instructions To the Cook riffs off of Eihei Dogen’s essay, mixing Bernie Glassman’s autobiography with practice points and Zen instruction.

Instructions to the Cook: A Zen Master’s Lessons in Living a Life That Matters by Bernie Glassman & Rick Fields is available from Shambhala Publications.

If you want a taste, a PDF can be found on Terebess.

The title Ways of Seeing is an homage to the continuing inspiration of the BBC TV series and book by John Berger.

Share your results and reflections in the comments. I’d love to hear from you.

I always know I’m going to find something nourishing and fresh in your newsletters, Sal, but something in the talk of greens instructed me in a way I felt (and loved feeling) to the point where I find that Zen has suddenly become a beckoning path for me. I think I may like to try being soup in a Zen pot now.

Thank you, Sal. I find your essays on zen deeply useful and inspiring. They make me more present in my life.