Dear Friends

As some of you may know I’m teaching a course on the poetic essays of Eihei Dogen. Why Dogen? If you’re not around Zen all the time, his name and work may not be familiar. He is known as the founder of Japanese Soto Zen, but also as Japan’s greatest philosopher-poet. His works are sometimes said to take a lifetime of Zen practice to understand fully. And yet, there is some way in which his writings offer themselves immediately in their vivid images.

I’ll be teaching three of Dogen’s most beautiful and loved essays in the course: “Genjokoan” (Actualizing the Fundamental Point), “Sansuikyo” (Mountains and Rivers Sutra) and “Uji” (Time-Being). I’ve been spending my days with them.

For myself, I read these essays as poetry. There’s a very long tradition of Buddhist poetry, dating from the time of the Buddha’s life, and even before there was such a thing as Buddhism, back into the oral traditions of India. Poetry has been central to Zen and appears everywhere in the Chinese and Japanese tradition: in Koan collections, in commentaries, in the private writings of Zen teachers.

When I say that I read these essays as poems, I mean that I read them spaciously. I let the words find their way in me, and I find my way into the words. On one reading, particular words and phrases seem lit up, and later it may be very different moments in the writing. Often something Dogen says seems true to me, luminously true, but I can’t quite articulate why.

Zen claims for itself that it is a teaching beyond words, and I might say that in a way all poetry is like this. Poetry is made of words, but points to what cannot be spoken.

As I was preparing the course, I came across two recordings of contemporary Zen teachers reading the essay “Genjo Koan.” I was struck again by the beauty of its writing, and by the shimmering quality of simultaneous, paradoxical, clarity and mystery. I invite you to listen and see what happens for you.

— Sal

Roshi Joan Halifax reading Dogen’s Genjo Koan

Roshi John Daido Loori reading Dogen’s Genjo Koan

Genjo Koan — Actualizing the Fundamental Point

As all things are buddha dharma, there are delusion, realization, practice, birth [life] and death, buddhas and sentient beings. As myriad things are without an abiding self, there is no delusion, no realization, no buddha, no sentient being, no birth and death. The buddha way, in essence, is leaping clear of abundance and lack; thus there are birth and death, delusion and realization, sentient beings and buddhas. Yet in attachment blossoms fall, and in aversion weeds spread.

To carry the self forward and illuminate myriad things is delusion. That myriad things come forth and illuminate the self is awakening.

Those who have great realization of delusion are buddhas; those who are greatly deluded about realization are sentient beings. Further, there are those who continue realizing beyond realization and those who are in delusion throughout delusion.

When buddhas are truly buddhas, they do not necessarily notice that they are buddhas. However, they are actualized buddhas, who go on actualizing buddha.

When you see forms or hear sounds, fully engaging body-and-mind, you intuit dharma intimately. Unlike things and their reflections in the mirror, and unlike the moon and its reflection in the water, when one side is illumined, the other side is dark.

To study the way of enlightenment is to study the self. To study the self is to forget the self. To forget the self is to be actualized by myriad things. When actualized by myriad things, your body and mind as well as the bodies and minds of others drop away. No trace of enlightenment remains, and this no-trace continues endlessly.

When you first seek dharma, you imagine you are far away from its environs. At the moment when dharma is authentically transmitted, you are immediately your original self.

When you ride in a boat and watch the shore, you might assume that the shore is moving. But when you keep your eyes closely on the boat, you can see that the boat moves. Similarly, if you examine myriad things with a confused body and mind you might suppose that your mind and essence are permanent. When you practice intimately and return to where you are, it will be clear that nothing at all has unchanging self.

Firewood becomes ash, and it does not become firewood again. Yet, do not suppose that the ash is after and the firewood before. Understand that firewood abides in its condition as firewood, which fully includes before and after, while it is independent of before and after. Ash abides in its condition as ash, which fully includes before and after. Just as firewood does not become firewood again after it is ash, you do not return to birth after death.

This being so, it is an established way in buddha dharma to deny that birth turns into death. Accordingly, birth is understood as beyond birth. It is an unshakable teaching in the Buddha’s discourse that death does not turn into birth. Accordingly, death is understood as beyond death. Birth is a condition complete this moment. Death is a condition complete this moment. They are like winter and spring. You do not call winter the beginning of spring, nor summer the end of spring.

Enlightenment is like the moon reflected on the water. The moon does not get wet, nor is the water broken. Although its light is wide and great, the moon is reflected even in a puddle an inch wide. The whole moon and the entire sky are reflected in dewdrops on the grass, or even in one drop of water.

Enlightenment does not divide you, just as the moon does not break the water. You cannot hinder enlightenment, just as a drop of water does not crush the moon in the sky. The depth of the drop is the height of the moon. Each reflection, however long or short its duration, manifests the vastness of the dewdrop, and realizes the limitlessness of the moonlight in the sky.

When dharma does not fill your whole body and mind, you may assume it is already sufficient. When dharma fills your body and mind, you understand that something is missing. For example, when you sail out in a boat to the middle of an ocean where no land is in sight, and view the four directions, the ocean looks circular, and does not look any other way. But the ocean is neither round nor square; its features are infinite in variety. It is like a palace. It is like a jewel. It only looks circular as far as you can see at that time. All things are like this.

Though there are many features in the dusty world and the world beyond conditions, you see and understand only what your eye of practice can reach. In order to learn the nature of the myriad things, you must know that although they may look round or square, the other features of oceans and mountains are infinite in variety; whole worlds are there. It is so not only around you, but also directly beneath your feet, or in a drop of water.

A fish swims in the ocean, and no matter how far it swims there is no end to the water. A bird flies in the sky, and no matter how far it flies there is no end to the air. However, the fish and the bird have never left their elements. When their activity is large their field is large. When their need is small their field is small. Thus, each of them totally covers its full range, and each of them totally experiences its realm. If the bird leaves the air it will die at once. If the fish leaves the water it will die at once.

Know that water is life and air is life. The bird is life and the fish is life. Life must be the bird and life must be the fish. You can go further. There is practice-enlightenment which encompasses limited and unlimited life.

Now if a bird or a fish tries to reach the end of its element before moving in it, this bird or this fish will not find its way or its place. When you find your place where you are, practice occurs, actualizing the fundamental point. When you find your way at this moment, practice occurs, actualizing the fundamental point; for the place, the way, is neither large nor small, neither yours nor others. The place, the way, has not carried over from the past, and it is not merely arising now. Accordingly, in the practice-enlightenment of the buddha way, to attain one thing is to penetrate one thing; to meet one practice is to sustain one practice.

Here is the place; here the way unfolds. The boundary of realization is not distinct, for the realization comes forth simultaneously with the full experience of buddha dharma. Do not suppose that what you attain becomes your knowledge and is grasped by your intellect. Although actualized immediately, what is inconceivable may not be apparent. Its emergence is beyond your knowledge.

Mayu, Zen Master Baoche, was fanning himself. A monk approached and said, “Master, the nature of wind is permanent and there is no place it does not reach. Why then do you fan yourself?”

“Although you understand that the nature of the wind is permanent,” Mayu replied, “you do not understand the meaning of its reaching everywhere.”

“What is the meaning of its reaching everywhere?” asked the monk again.

Mayu just kept fanning himself.

The monk bowed deeply.

The actualization of the buddha dharma, the vital path of its authentic transmission, is like this. If you say that you do not need to fan yourself because the nature of wind is permanent and you can have wind without fanning, you will understand neither permanence nor the nature of wind. The nature of wind is permanent; because of that, the wind of the buddha’s house brings forth the gold of the earth and ripens the cream of the long river.

Written around mid-autumn, the first year of the Tempuku Era [1233], and given to my lay student Koshu Yo of Kyushu Island. Revised in the fourth year of the Kencho Era [1252].

— Translation by Kazuaki Tanahashi

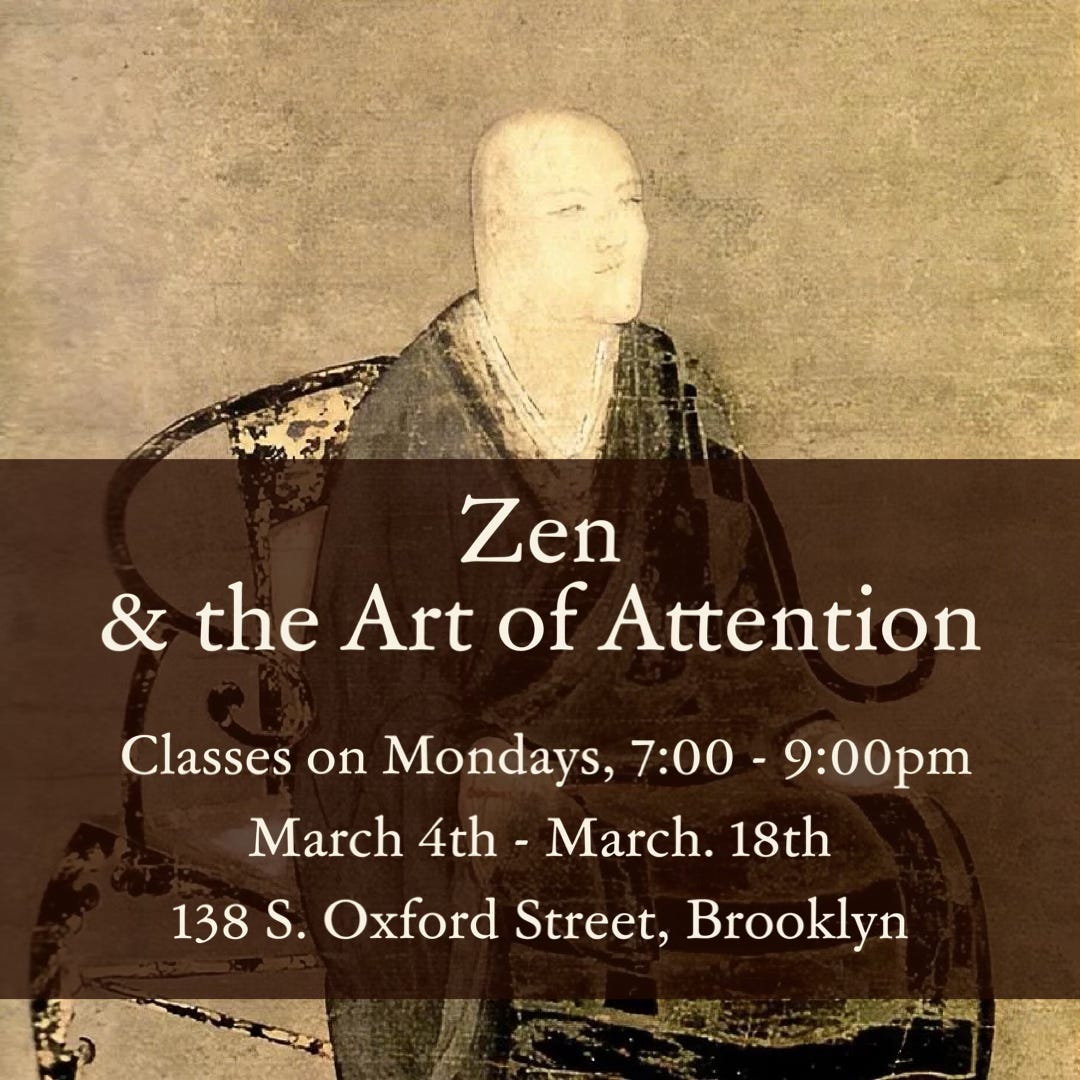

Zen and the Art of Attention

3 Mondays 7-9 pm starting March 4th

The Strother School of Radical Attention

138 S. Oxford Street, Brooklyn

Attention and distraction can seem like new problems—part of our distinctively contemporary life—yet there is a rich history of contemplative practice stretching back thousands of years and across continents. Almost all spiritual traditions include some form of quiet sitting and contemplation; these practices could be considered technologies of attention, part of our collective cultural heritage. Can they offer new ways of relating to the commercialized attention economy we live in today?

This course offers an introduction to one such tradition, Zen Buddhism, as seen through the enigmatic and poetic essays of the great thirteenth-century Zen teacher, Eihei Dogen. We will engage in close reading of three key essays, “Bendowa” (“On the Endeavor of the Way”), “Genjokoan” “Actualizing the Fundamental Point”) and “Uji” (“Time-Being”). The course will culminate in an Attention Lab which will include an opportunity to experience the practice of Zen meditation.

March 4th - March. 18th

Mondays, 7:00 - 9:00pm

Strother School of Radical Attention

138 S. Oxford Street, Brooklyn

The course will culminate in a free, public Attention Lab.

Cost: $200 (sliding scale from $160, some full tuition scholarships available).

Further adventures and new ways of seeing can be found in my book, The Uses of Art.

Artist Sal Randolph’s THE USES OF ART is a memoir of transformative encounters with works of art, inviting readers into new methods of looking that are both liberating and emboldening.

Dazzlingly original, ferociously intelligent.

— Michael Cunningham

A joyful, dazzling treasure-box of a book.

— Bonnie Friedman

Here’s a guide, to waking up, over and over again.

— Roshi Pat Enkyo O’Hara

I just opened this…It came at a time when my inbox was way too full. So sorry I missed that class!

Thank you for placing these beautiful passages here for us, Sal. I am struck by the similarity of some of these comparisons to Jesus' parables (the lilies in the field etc) and I'm sure if I knew other religions more intimately there would be other stories and fables and metaphors about the transcendent or things beyond immediate apprehension to find there too.

It has reminded me of how my initial desire to write came from the poetry of the Bible, although I am no longer a practising Christian.

The one that spoke to me here was the moon on the water but, like you, I could not express what it 'means', only that it resonates, and suggests meaning to me. It also echoed a favourite line from Yeats' poem The Stolen Child:- "In pools among the rushes/that scarce could bathe a star".