Dear Friends,

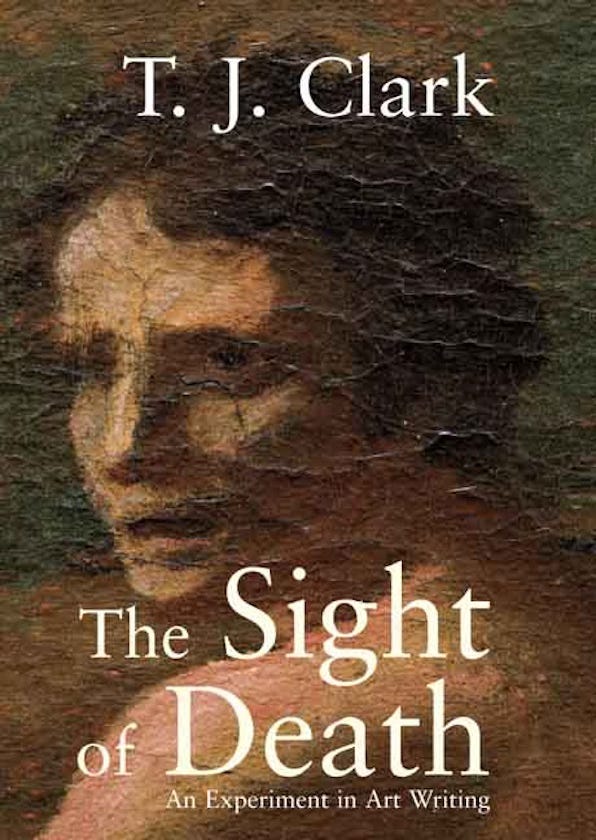

Years ago I encountered a remarkable project undertaken by the art critic T. J. Clark. In his book The Sight of Death he set himself an experiment: to look again and again at a painting and offer his daily notes as a record of that seeing. One painting became two: Clark’s story centers on encounters with a pair of interconnected paintings by Nicholas Poussin, both painted between 1649 and 1650: Landscape with a Calm, and Landscape with a Snake.

I’ve always felt a romantic pull towards the idea of return. Looking at something over and over finds you, the seer, fresh each time; it is as much mirror as window.

Here are a few words from T. J. Clark on repeated viewing, and a brief excerpt from The Uses of Art where I have my own encounter with Poussin’s Landscape with a Calm. I hope you’ll take these as inspiration to embark on your own project of seeing again and again.

& for those who have joined us recently, welcome! “Ways of Seeing” is a series of inspirations and practical exercises for deepening attention and engaging with art and the world. Let me know your own experience in the comments.

— Sal

T. J. Clark from The Sight of Death

[…] Certain pictures demand such looking and repay it. Coming to terms with them is slow work. But astonishing things happen if one gives oneself over to the process of seeing again and again: aspect after aspect of the picture seems to surface, what is salient and what incidental alter bewilderingly from day to day, the larger order of the depiction breaks up, recrystallizes, fragments again, persists like an afterimage. And slowly the question arises: What is it, fundamentally, I am returning to in this particular case? What is it I want to see again? Can it be that there are certain kinds of visual configuration, or incident, or play of analogy, that simply cannot be retained in the memory, or fully integrated into a disposable narrative of interpretation; so that only the physical, literal, dumb act of receiving the array on the retina will satisfy the mind?

from The Uses of Art

Recognition and Surprise

I’m at the Getty in Los Angeles having my first real sight of Poussin’s Landscape with a Calm: a simultaneous shiver of recognition and surprise. I know you, but I’ve never seen you. Neither the reproductions in T. J. Clark’s The Sight of Death nor the presentation on a classroom projection screen have prepared me. The painting is somehow completely different from its image, as the picture of a face is not a face. If I hadn’t spent so much time with the image, I might never have seen the difference.

The painting is both lucid and paint-y, meaning you can see what it shows more clearly than in the photographs, but you can also see the direct artifice of the paint. For instance, small horizontal strokes caress the trunks of the twinned trees to the right, giving the bark a silver highlight. Or the dark areas of the painting, intentionally shadowed and obscured but perfectly visible if you are looking directly at them.

The painting is hung so that the horizon is at eye-level in a room with soft green walls. Overhead the skylight lets in fil- tered light from the bright hundred-degree day, but there are also spotlights, both warm and cool, trained on the painting. It is hung by two wires from the ceiling and has a heavy gold frame, less ornate than the ones nearby, an outer rim of plain gilded molding and an inner rim of repeated leaf pattern.

I hear the squeaking of sneakers on the floor as a school group leaves the room, a long squeal of baby stroller wheels, a conversation in Japanese, “Kore, ne?” Each museum has a distinctive sound; the Getty’s is the squeaking of shoes. Hardly anyone speaks except the waves of schoolchildren. The fabric walls absorb as much noise as they can.

After a long time spent trying to see things I can’t be in front of, this is a simple relief.

I leave for a while and come back again. Sitting on the gallery’s unusually comfortable sofa, I bring up the Getty’s image on my laptop and compare it to the painting. The effect of the digital image is nothing like the painting’s—the colors must in truth be unreproducible. The ochre side of the building comes out greenish on the screen, the fire to the right is almost invisible because the little pop of orange is dimmed and does not catch the eye. The crag above is muddled and muddied, the lake less blue.

One of the guards stops to look at it, gazing for a long time close up, tilting his head this way and that.

A Place to Stand

A strange thing happens if I keep my eyes on the painting—it seems to brighten, as if the clouds in the painting are parting slightly.

Clark believes the painting depicts the end of day, and his argument has the force of logic (he sees the cows as heading home), but to me the light feels like the calm of early morning, the stillness before the day properly beings.

The painting is both a depiction and a body in its own right. It is not a window. And even a window is not a window. The painting mediates what it depicts, but it is also, immediately, itself. Clear blobby little brushstrokes for each leaf. Tiny figures no bigger than leaves, whole buildings in the background no bigger than leaves.

The goatherd’s body gives you a place to stand, but the view is not his. The view is from farther back and higher up the hill.

The sky is full of energy harnessed in the contrast, brightness, and shadow in the thick cumulus cloud forms. Even from across the room, it is hard to see where the cloud ends and the mountain begins, in the same colors but with forms more angular and craggy.

A Calm

After spending time with the painting, I go to eat some lunch and sit down looking out over the dry hillsides. To my surprise, I don’t reach for my phone to read something. Instead, I simply sit a long while looking out. A great calm has blossomed in me unawares.

It must have been, it can only be, the calm of the painting.

The hills I am seeing bear some superficial echo of the hills in the painting. I look at the pines and firs and study their leaves in the light. Above, the pale Los Angeles sky, shading towards white where it meets the hills. Nothing stirs. One car makes its way down a dusty slope. After a time, two hawks circle up.

Like the painting’s, the calm I see is no calm. In the houses of the wealthy that perch on these upper slopes, surely there are medical emergencies, angry teenagers, financial anxieties, and existential doubts, as there are in any inhabited place. Just as in the painting there are urgencies: the horse leaps away to the left and a small fire blazes behind the building to the right, burning brush or classical trash. The clouds are frozen in their slow-motion tumult. Yet all these only reinforce the stillness of the painting, the stillness that emanates from it and seems to have passed into me. Where, precisely, does it lie?

If you saw through the painting to what it depicts, you might place the calm quite logically in the blue of the lake, where the sky appears unbroken, or you could place it in the body of the goatherd who leans on his stick in the shadowed foreground. You might place it in the light that catches the broad blocks of the building, castle, or villa, holding the flat planes of its geometry. Calm might seem to issue forth from that wide patch of almost monochrome pale ochre.

But I wonder. It’s true the painting does depict ‘a calm’ (French: Un Tem[p]s calme et serein—calm and serene weather). And yet it seems to me that it is the paint itself that is calm, or gives off calm. Its patience, ease, exactitude

Exercise:

Prepare to Return

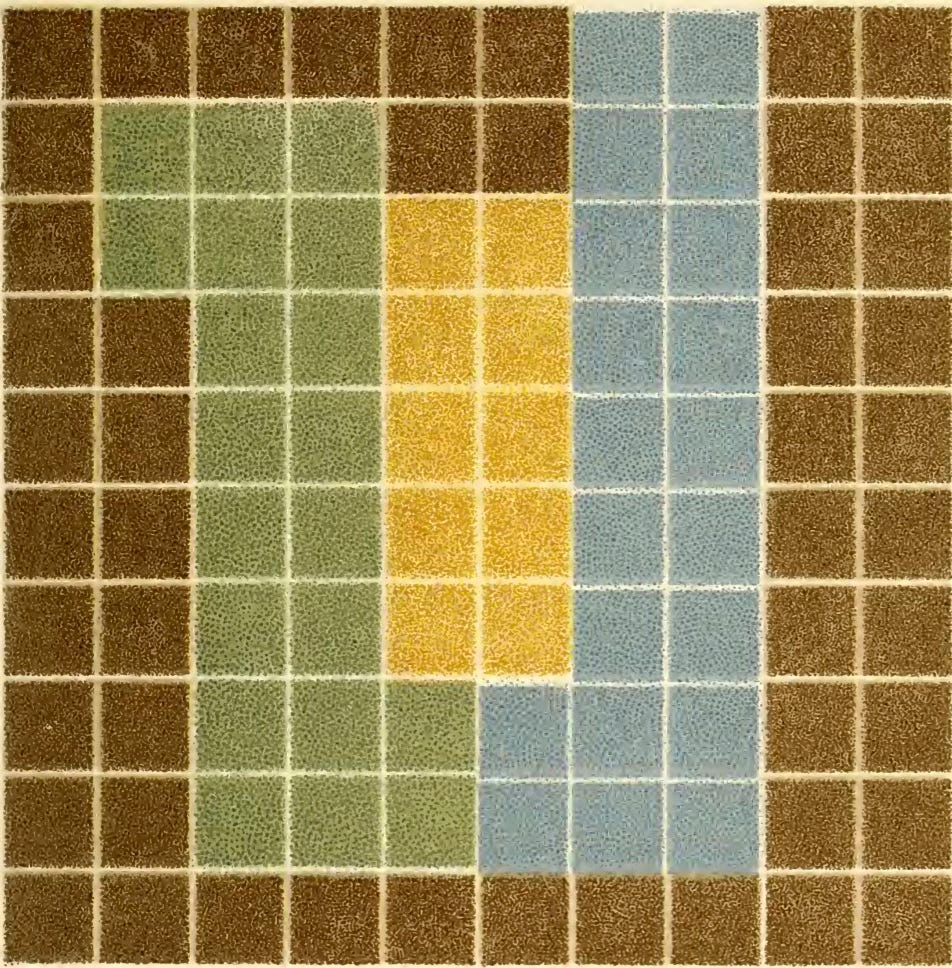

Find a work of art you can visit again and again. Maybe you have a free museum in your city, or you have a membership that lets you visit any time you like. Maybe there’s something you pass as you go from place to place, a public sculpture or a subway mosaic. Maybe there’s a work of art you like at a friend’s house (for this exercise, it’s best to use something you don’t live with daily). Or maybe there’s a work you’re willing to travel to over and over again, like a pilgrimage. It could even be a work you return to in reproduction in the pages of a book.

Look, and Look Again

Bring a notebook with you on your adventures. After you’ve spent time with the work, write down some notes or make sketches. What do you notice on this particular encounter? What caught your eye and your mind? Include your own mood, and your own experience. Let your motto be: include everything.

Do this for as long as you can, but the goal of a year is a nice one to begin with.

As with all of these “Ways of Seeing,” the initiating impulse is to expand our possibilities for engaging with works of art and deepening attention to everything around us. These exercises are perfect for time spent in museums, galleries, and studios. You can also bring them into the rest of your life and experiment with streets, libraries, parties, landscapes. Try them as writing or art-making prompts.

These practices work best if you give them some time.

As ever, interpret these instructions freely and intuitively. Make them your own.

The Sight of Death

T. J. Clark’s The Sight of Death is available from Yale University Press.

You can try another exercise of return with poet and artist Etel Adnan here:

The title Ways of Seeing is an homage to the continuing inspiration of the BBC TV series and book by John Berger.

Share your results and reflections in the comments. I’d love to hear from you.

Further adventures and new ways of seeing can be found in my book, The Uses of Art.

Artist Sal Randolph’s THE USES OF ART is a memoir of transformative encounters with works of art, inviting readers into new methods of looking that are both liberating and emboldening.

Dazzlingly original, ferociously intelligent.

— Michael Cunningham

A joyful, dazzling treasure-box of a book.

— Bonnie Friedman

Here’s a guide, to waking up, over and over again.

— Roshi Pat Enkyo O’Hara

I wonder what's in the air—I just took on a similar project earlier this month, to go look at a painting again and again. Loved your writing.

Beautiful post, Sal! I was moved by your account of truly seeing the painting at the Getty and its aftermath. There a sculpture of a heron I return to often in a pond near the library. I’m going to try this exercise on her.