Dear Friends,

What happens when we look and then look again, daily, weekly, monthly for years, for a lifetime?

The painter and poet Etel Adnan fell in with a mountain, Mount Tamalpais on the coast of California north of San Francisco. For many years she lived in a place where she could see the mountain every day, and she frequently visited in order to know its trees and trails more intimately. Later, she returned to the mountain in memory and imagination, painting it over and over again. She once described it as the most important person she knew.

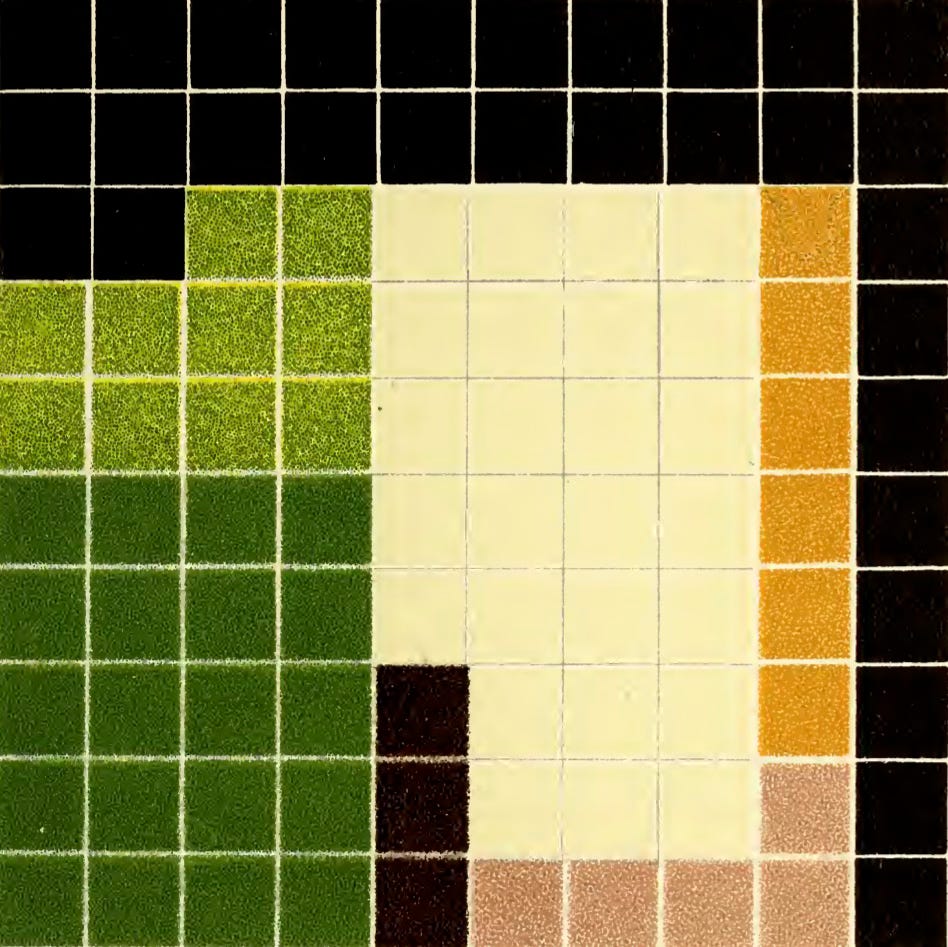

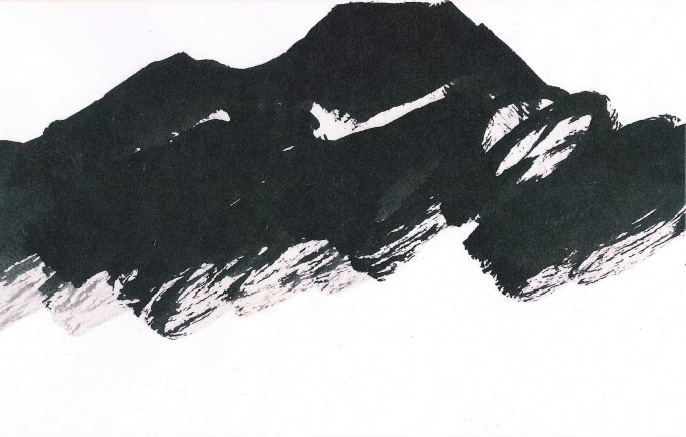

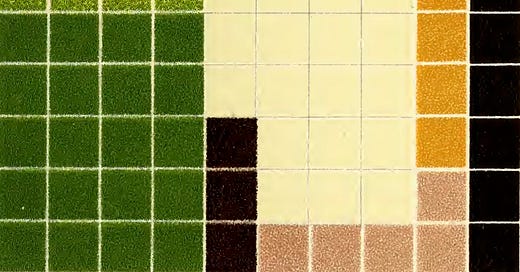

I first saw Adnan’s work in 2012, when it was exhibited as part of Documenta 13, in Kassel, Germany. I entered a room full of small paintings, abstracted landscapes rendered in blocks of color. The paint felt like a materialization; the images were simultaneously repeating and unique. The most frequent images were of Mount Tamalpais, which lingered in my imagination as a mythical place.

More recently, I discovered Etel Adnan’s much-celebrated poetry and her early book of poetic prose, Journey to Mount Tamalpais. Written over many years, it records her experience “making” the mountain, and in turn being made by it.

This week we experiment with Adnan’s particular form of deep seeing: turning ourselves again and again to the same object of attention. By looking at one thing over and over we discover its changes, and we discover that we are selves are new each time we look.

For those who have joined us recently, welcome! “Ways of Seeing” is a series of inspirations and practical exercises for deepening attention and engaging with art and the world.

— Sal

P. S. I’m taking time off next week, so I’ll see you again at the beginning of May.

Mount Tamalpais

From Etel Adnan, Journey to Mount Tamalpais.

Sometimes, they open a new highway, and let it roll, open wide the earth, shake trees from their roots. The Old Woman suffers once more. Birds leave the edges of the forest, abandon the highway. They go up to mountain tops and from the highest peaks they take in the widest landscapes, they even foresee the space age.

The condor is dying. He used to live on the top of Tamalpais. His square wings used to carry him all over the area: the hills were moving beneath him with silent pride. He used to cut through the clouds like fearful knife. At certain seasons he used to carry the moon between his claws. Now we took over his purpose. We are the ones to go to the Mountain.

This morning I took the card table and put it out on the deck, under the pine trees. On a piece of paper shadows fell. I tried to catch their contours but they were slowly moving, all the time. They made me think of sidewalks on which people pass, swiftly. And the big mountain sent a wild smell of crushed herbs into the air making everything feel slightly off.

Like a chorus, the warm breeze had come all the way from Athens and Baghdad, to the Bay, by the Pacific Route, its longest journey. It is the energy of these winds that I used, when I came to these shores, obsessed, followed by my home-made furies, errynies, and such potent creatures. And I fell in love with the immense blue eyes of the Pacific: I saw its red algae, its blood-colored cliffs, its pulsating breath. The ocean led me to the mountain.

Once I was asked in front of a television camera: “Who is the most important person you ever met?” and I remember answering: “A mountain.” I thus discovered that Tamalpais was at the very center of my being.

Year after year, coming down Grand Avenue in San Rafael, coming up from Monterey or Carmel, coming from the north and the Mendocino Coast, Tamalpais appeared as a constant point of reference, the way a desert traveler will see an oasis, not only for water, but as the very idea of home. In such cases geographic spots become spiritual concepts.

The pyramidal shape of the mountain reveals a perfect Intelligence within the universe. Sometimes its power to melt in mist reveals the infinite possibilities for matter to change its appearance.

I watch its colors: they always astonish me. When it is velvet green, friendly, with clear trails, people and animals are invited to climb, to walk, to breathe. When it is milky white it becomes the Indian goddess it used to be: a huge being with millions of eyes hidden beneath its skin, similar to the image of God I used to have in my childhood days. When it is purple, it radiates.

About three in the afternoon, the mountain starts to swell. The colors and the shadows sharpen. The volumes come into fullness. It all looks so mysterious.

This living with a mountain and with people moving with all their senses open, like many radars, is a journey…melancholy at times: you perceive noise and dirt, poverty, and the loneliness of those who are blind to so many things…but miraculous most of the way. Somehow what I perceived most is Tamalpais. I am “making” the mountain as people make a painting.

Exercise: The Mountain

Take these words of Etel Adnan’s as your guide:

Once I was asked [..]: “Who is the most important person you ever met?” and I remember answering: “A mountain.” I thus discovered that Tamalpais was at the very center of my being.

Choose an object of attention, or let it choose you. Take a fresh notebook and dedicate it to this object, this mountain. Begin one day with a few words or notes. Write what you see and what you feel as you give the object your full attention.

Return another day, or another week and write freshly. Try not to read what you wrote last tine, instead observe the object and observe yourself closely as you are right now. Be precise about what you record. Let dreams, thoughts, memories enter as they will.

Keep going, day by day and week by week until the notebook is filled.

As with all of these “Ways of Seeing,” the initiating impulse is to expand our possibilities for engaging with works of art and deepening attention. These exercises are perfect for time spent in museums, galleries, and studios. You can also bring them into the rest of your life and experiment with streets, libraries, parties, landscapes. Try them as writing or art-making prompts.

These practices work best if you give them some time, at least twenty minutes or a half-hour. This is easier to do if you set a timer.

As ever, interpret these instructions freely and intuitively.

Share your results and reflections in the comments. I’d love to hear from you.

Etel Adnan

Journey to Mount Tamalpais by Etel Adnan is available from Litmus Press.

You can read a longer excerpt here.

The full book can also be “borrowed” and read from the Internet Archive.

Etel Adnan’s paintings of Mount Tamalpais as exhibited at Calicoon Fine Arts in 2012.

Etel Adnan’s paintings as exhibited at Documenta 13 in Kassel Germany in 2012.

Etel Adnan on lightning-strike paintings and words as gestures:

Further adventures and new ways of seeing can be found in my book, The Uses of Art.

Artist Sal Randolph’s THE USES OF ART is a memoir of transformative encounters with works of art, inviting readers into new methods of looking that are both liberating and emboldening.

Dazzlingly original, ferociously intelligent.

— Michael Cunningham

A joyful, dazzling treasure-box of a book.

— Bonnie Friedman

Here’s a guide, to waking up, over and over again.

— Roshi Pat Enkyo O’Hara

I’m glad it felt right to you!

I feel so happy and moved, reading this tiny essay about Etel Adnan and hearing the video of Adnan discussing how she came to be a painter. I realize, too, that a tree outside my window here in Brooklyn has chosen me, and I have been witnessing her for many years, often taking notes. Thank you, Sal Randolph, for this exquisite meditation and also instruction. I love any assignment that begins, "Get a new notebook." And I love how reading your Substack both centers me and fills me with joy.