Dear Friends,

This talk is part of what has become a series of posts on the subject of care as one way we can respond to the present national moment.

I hope you are holding true.

— Sal (aka Gessho)

Video & Audio: Holding True

Video and podcast audio here.

Transcript: Holding True

[This transcript has been lightly edited.]

This National Moment

Today I want to talk a bit about the present moment, our national moment here in the United States, and how I am trying to find a kind of orientation within what's going on.

As I came in this morning, I realized I was feeling much less prepared to speak than I usually do, even though I've worked at it. My friend, Bokushu, said, well, maybe it's good to be less prepared. And maybe it is. So maybe you'll get a little bit more raw me than usual.

I also realized that the reason I'm less prepared than usual is that I'm afraid to speak about this. It's scary. And everything that's going on has been, for me, upsetting and frightening. It's been difficult to find a way to respond and to navigate inside it. I feel very much like I don't know what to do. And I don't know what to say.

Not Knowing

For those of you who have been around here for a while, you may have heard that the three pure precepts, as expressed by the Zen Peacemaker Order, which is part of our larger community, are: not knowing, bearing witness, and responsive action.

So you think we'd be kind of good at not knowing by now. But not knowing can be scary. And I'm feeling that very much. Not the “not knowing,” but the actual not knowing feels very different.

Today, when everybody began to gather in the space and online, I realized I felt a bit differently. Instead of some kind of abstract talk that I was going to give, suddenly I was speaking to you.

So that changes everything. Even if I don't know what to say, we're here together in this mess.

Care as a Form of Attention

Today I want to talk about care.

Care is a way of orienting ourselves, care is a form of attention, and care is possibly a politically potent thing. Care is a bit different from our usual kinds of political experience and action, or mine, anyway, but care is one of the ways that I'm orienting myself now.

The work that we've been studying during this Ango (intensive practice period), is Instructions to the Cook beginning with Eihei Dogen's essay from the 13th century.

Dogen is talking very literally about the cook in a monastery in that essay, and how that cook should be thought of, treated, and how they should act. But we're also taking this collectively as if we are all the cooks in our own worlds. The way the cook tends to the kitchen of the monastery, we are all tending to our own areas of responsibility in our life.

Joyful, Nurturing, Magnanimous Mind

The attitude that Dogen talks about near the end of the essay, is a kind of mind which is joyful, nurturing (or parental), and magnanimous.

That's the way to approach the spheres of responsibility that we have. And for me, all of these are aspects of the mind of care. So the joyful mind is grateful and buoyant. (We all know what it's like, I think, when somebody cares for you who doesn't really want to, who feels resentful. So it's the opposite of that. It's a really genuine gift of care.)

The nurturing mind, the parental mind, is care, of course, in a literal way. also, it reminds you when you leap forward to care for something that you love. When I see the face of my dog, I'm like, oh, that little snout, those little paws, that fur, I love my dog.

There are many things in my life, many people in my life that I love. The way in which when you just see some something or someone you love, you feel that instant kind of joy and connection. That connection, that non-separation, is part of the magnanimous mind.

Magnanimous mind is large mind, the self that includes all other beings, the non-separate self, the empty self.Dogen reminds us that the large self is stable, and not so easily pushed around by any one thing that's happening.

We're in a situation where our attention is being jerked around a lot, if you happen to be looking at the news at all. And some people I know aren't, during this time, looking at the news at all. It's too painful. The kind of attention that's easily moved from place to place is very different from the kind of attention of care.

Care as Steady Attention

Care requires a great steadiness of attention.

It brings your focus into your own sphere of responsibility. Your focus is where your action is. I think that that kind of attention is worth cultivating, even in a crisis, maybe especially in a crisis.

When you care for something, like taking care of a child, or a pet, or an apartment, or a garden, or if you're at work taking care of a document, or a file, or if you're writing, whatever you're doing, it requires you to hold that thing in mind in a particular way and return to it if your attention is taken away. Return to it just the way if you're sitting in Zazen and you find yourself distracted. Your task is simply to return to the breath, to the moment, to count in the breath.

There's a kind of creativity in care as you're attending to something real in front of you. Things go awry, but you creatively find ways of responding. And that creativity, I think, is really helpful to us right now.

I feel like now is a time for all of us to consider caring for what we care about.

Mierle Laderman Ukeles

I've been being inspired by this particular artist named Mierle Laderman Ukeles, who I'll tell you a little bit about.

She was born in 1939, and she's currently alive; she's 85 or 86. She went to art school in the 60s at Pratt, here in New York.

She made sculpture and assemblage. That's what was really happening at the time. One of her teachers was Robert Rauschenberg. And she was making these sculptures that involved stuffing things into fabric, and that required a lot of work, but they also fell apart, and so they also required a lot of maintenance.

When she was done with art school, she and her husband had a baby. Suddenly, her life was completely different, and all of her maintenance energy was being put into keeping this child alive and well.

She said, in an interview,

It was a time of crisis for me. I mean, I wanted that baby. It wasn’t that someone pushed me into having a baby. But all my heroes, the artists I was trying to be like—Jackson Pollock, Marcel Duchamp, Mark Rothko—didn’t have to deal with the maintenance of motherhood. Here I was changing diapers, saying to myself, “Where are you, Jackson? Where are you, Marcel?” I felt like they abandoned me. They had nothing to say to me. They wouldn’t be caught dead doing what I was doing as a mother. I felt like I was falling.

Falling into that kind of not knowing.

And then she goes on to say,

One day, it was October 1969, I had an epiphany. I said to myself: You’re the boss of your freedom. You’re not a copier of Marcel, who can’t help you anymore. If you’re the boss of your freedom then you have the right to name anything art. Marcel gave me that right. So that’s how I turned my maintenance work into maintenance art. That was it. It was a way to keep my life together. I said to myself: I’m an artist. I need to be who I am, and this is who I am.

Life and Death, Development and Maintenance

Then, in a kind of white-hot moment of inspiration and rage, she wrote a manifesto for what she called Maintenance Art. She was claiming all of the acts of her actual life as a new form of art in that manifesto.

She began it by laying out a couple of ideas that I think are helpful for us. One is she distinguished between what she called the death instinct and the life instinct. And this is 1969, so Freudian thought was maybe a little bit more in the air than it is now.

She describes the death instinct as “separation; individuality; Avant-Garde par excellence; to follow one’s own path to death—do your own thing; dynamic change.”

And the life instinct as “The eternal return, the perpetuance and maintenance of the species, survival systems and operations, equilibrium.”

She's making a critique of the avant-garde that she had loved and which failed her in this moment.

She also talks about two separate systems, which she calls development and maintenance:

Development: pure individual creation; the new; change; progress; advance; excitement; flight or fleeing.

Maintenance: keep the dust off the pure individual creation; preserve the new; sustain the change; protect progress; defend and prolong the advance; renew the excitement; repeat the flight;

She's making a critique of our whole society, but also of art’s obsession with change, newness and the individual. This also made me think about Silicon Valley's ethics of explosive growth and of acceleration, of destruction, of dominance. They're saying move fast and break things. And though Silicon Valley had idealistic origins, it's really been taken over by its own vast wealth, and that optimism has been transformed into a kind of ruthlessness.

Right now, that same thinking is being applied to our government. Moving fast and breaking governments is what's going on. It remains to be seen how far they will succeed.

The economic system we live in, which is also an ethical system, is capitalism. Capitalism doesn't care, and it can't really care. It has other things it has to answer to, which are different from what any individual person might love or might need.

If we want to care about things, we can't rely on these larger systems to care about them for us, or care for them for us.

Maintenance Art

Mierle Laderman Ukeles said,

I became a maintenance worker because I became mother. The thing about maintenance is that if you decide that something has value, then you want to maintain it. You have to do a series of tasks to keep it alive. I loved that baby; I fell madly in love with that baby. But I didn’t know anything about being a mother, about how to make sure that my child was healthy and robust. Whether it’s a child, an institution, or a city, it’s all the same: if you want them to thrive, you have to do a lot of maintenance—a whole lot.

The artwork that she went on to do, and still does to this day, has really all focused on this idea of maintenance.

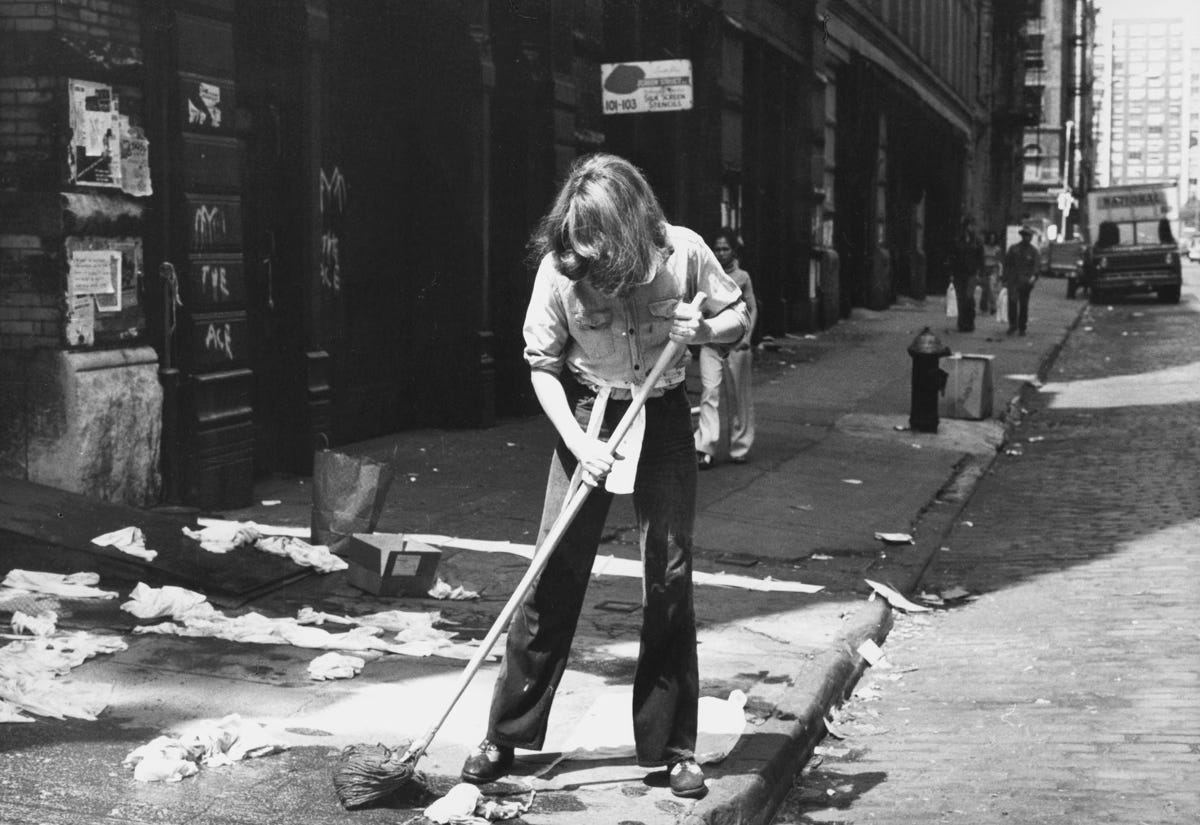

One thing that happened is that she became the artist in residence of the New York City Sanitation Department. It was an unsalaryed position, but she did that for about 40 years. She did many projects with the workers of the Sanitation Department, to show, to value what it was that they did.

One of the projects was called Touch Sanitation. Over the course of a couple of years, she touched the hand of every single sanitation worker. She wanted to do this because we think of those hands as being made dirty, somehow, by that garbage that they touch. She wanted to shake hands with every person, look them in the eye, and thank them for their work. That was about like nine or ten thousand people. She also collected their stories and shared them in exhibitions.

She was part of exhibitions where her artwork was simply to clean the space of the institution and to visibly show its cleaning and its maintenance. She also would interview some of the people who did that as their regular work and showed aspects of their work to the public. She also organized giant outdoor ballets of maintenance and construction equipment, moving gracefully in beautiful patterns.

So she did many different kinds of work, but to show the skill, the importance, and the value of maintenance work, both her own and all the people who do that as their regular task. I'm finding her very inspiring in the moment.

What Can We Do?

This brings me back to the question of kind of what can we do?

Who are we in this story?

The thing that I would like to invite you to do is to pay some close attention to your actual ordinary life, and to notice what it is that you do.

What are your spheres of responsibility? What are you taking care of?

Think about the way in which what you're already doing in your life, what you're already taking care of, your tasks, all embody your deepest values. (If you find that they don't, maybe it's a time to consider that.)

But I think for many of us, what we do ordinarily is very important, actually.

Caring for the Dharma

I’ve been noticing that one of the things I do is take care of this space, this zendo.

I'm only one of many, many people who do. I'm just trying to guess how many. Is it 75? Is it 100? Different people who do some or another task to keep this online space and this physical space open. Maybe they pick up the mail, or they clean the space, or they open it for sitting. or open it online and host it online. Or they process the Dharma talks so that they can be posted later. Or they give the Dharma talks, or they take out the trash. There are just so many tasks and so many people who make this space alive.

This is one of those bases of care that I'm noticing.

I also feel like every single person who shows up, whether it's the first time you've ever been here, whether you only come once, whether you're just here right now, you're in a very literal way, right now, supporting me. And you are supporting the maintenance of the Dharma.

This is what we say at the beginning of the Dharma talk, when chant, the Gatha on Opening the Sutra, “Now, we maintain this.” Together, we maintain the Dharma.

The teachings have been maintained for us for thousands of years, by countless acts, many very mundane acts, of people who valued this teaching, and this practice, and this awakeness. I'm feeling especially grateful to them, for this beautiful maintenance.

I’m feeling grateful to all of you for that maintenance.

Your Ordinary Work is Important

As you look around your life, is there anything that is in your life that you directly care about, that's currently under threat of violence, or of denigration, of legal sanction? There's so much that's under threat right now, I'm guessing the answer is probably yes, for most of us.

That makes the work that you do especially important.

Do you work in health care? Health care of all kinds is under threat.

Are you a scientist? Science is under threat.

Do you work in a university? Universities are under threat.

Do you teach children? The the whole idea of education is under threat.

Do you work in a bookstore or a library? Do you write? Do you make art? Do you help administer something? Do you work in a national park? There are so many kinds of tasks which very directly bear on what is being threatened right now.

These areas where we have direct responsibility also give us a much more direct and intimate knowledge.

Intimate Knowledge

There are things that are happening out there, (though we know that in some larger absolute sense, there's no “out there”) that you're not directly interacting with in some way every day.

It's hard to know much about those things, really. You can find out about them through the news, but it's mediated. You literally find out through the media.

There's an im-mediate kind of knowledge in your sphere of care. This is where we find what is true for us both in our hearts, what is our true feeling, what is our true knowledge.

I think it's important to gather that into ourselves and to stand from that kind of direct knowledge.

If there's anything that we value, we cannot not leave it to the hands of politicians, however well-meaning some of them may be. We don't want to leave it in the hands of our capitalist system.

We want to hold what we value in the hands of love—the hands that are joyful, nurturing, magnanimous—our actual hands.

What We are Called to Do

We are, called to do all the kind of traditional forms of political action right now: contacting your representatives, organizing locally and nationally, maybe protesting, all of those things are familiar and are certainly going to be needed.

However, I think we should also look at what we're actually doing in our lives as itself politically important and politically potent.

These may be things that we ordinarily don't think of as political, like maintenance and care, protection and preservation. Those are values that people on the left have often ceded to what we used to call “conservatives,” the values of keeping alive something important from the past.

I don't think we should cede those values at all right now. I think we should stand with them.

In the Heart of Not Knowing

But this are just what I think, right? This is just what I think today.

I feel really in the heart of this change and in the heart of not knowing. So, I especially say that it's your own heart that you need to consult. Not my words.

I want to close with some thoughts from Rebecca Solnit, who wrote these words just after, just on November 6th.

She said,

The fact that we cannot save everything does not mean we cannot save anything. And everything we can save is worth saving. Right now, good friends and good principles are worth gathering in. Remember what you love. Remember what loves you. Remember in this tide of hate, what love is. The pain you feel is because of what you love.

I think now is the time for all of us to care for what we care about, and to hold steady with our values and convictions and loves. To hold steady with ourselves and our communities, to hold true.

What are some of your spheres of care? I’d love to hear from you.

Related Posts

Today’s talk builds on two recent posts of mine exploring the forms of attention inspired by Dogen’s “Instructions to the Cook.”

Ways of Seeing: Care

Every time I gather with people I love, the question arises: what should we be doing? Certainly, we’re in a collective emergency, and emergency demands a response, doesn’t it? Eight years ago, we were all in the streets, but now we’re not. What does that mean? For myself, I have a clear feeling, a take, if you will. One inspiration for it is the work of artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles, which has slowly shifted my understanding about what kinds of effort are most important.

Ways of Seeing: The Cook

Today I’m heading up the Hudson to the Village Zendo’s annual winter retreat for a week of silence. Our group will be collectively reading a 13th century essay by Eihei Dogen, one of the founders of Soho Zen in Japan. As a young monk Dogen traveled from Japan to Song Dynasty China in search of answers to his biggest spiritual question: if we already have a Buddha nature, an enlightened self, why is it that we practice?

Thank you for this!!! It is the sanest response to these times. I want to send it to everyone I know. The message of finding what we care for and raising our care and preservation of it to an art firm is brilliant and so generative in these days. I am thinking about my day with so much more love and devotion to the world around me. I can’t say that fear, like any force, doesn’t wobble my efforts from times to time, but this little boat is under way. Thank you. Thank you.

This was all so excellent and uplifted my heart today and in this great big unknowing that we’re in. Thanks, Sal.