Dear Friends,

Not long ago, I shared my love for composer Pauline Oliveros’ practice of Deep Listening. This week, I offer a recent dharma talk where I investigate her life and work more fully, and consider Deep Listening in relation to Zen koans about sound.

In a bit of an experiment, I’m putting the video of the dharma talk first, with a podcast option just below. This was a spoken talk, not something read from sheets of paper, so it will flow better if you watch or listen. There’s also a lightly edited transcript, in case you’d rather read.

— Sal (Gessho)

Video: Deep Listening

Podcast

As an alternative, you can listen to the podcast version of this talk here.

Transcript

Listening

Hi everyone. My name is Gessho [my dharma name], and I'm a senior student here at the Village Zendo.

It's really good to be here — gathered with some friends of the way on a chilly autumn night. It’s good to gather with you online, and even gather with the people who are not with us in time, who someday might be finding these words and listening to them. So, thank you.

Listening is in fact my subject tonight. I want to share with you some stories about the composer Pauline Oliveros, who is known mostly for a practice of deep listening. I’ve been immersing myself in some aspects of her work that I want to talk about this evening.

I'm excited to do that, but I wanted to start by putting us in a Zen frame of mind. There are a couple of good Zen stories about people who have awakened on hearing a sound. Both of these are from a book called Zen's Chinese Heritage by Andy Ferguson — it's a gathering of of traditional stories, many of which are not in the koan collections.

Koans of Listening and Hearing

The first one of these is about a teacher named Xiangyan Zhixian. When he was a student, he was known as being extremely studious, learning everything about the Zen traditions and stories and the literature. But his teacher would say to him, “when you speak, I hear other people's words coming out of your mouth. Where are you? What is your original face?” Show me you!

Xiangyan was baffled. He was stopped there, stuck and very frustrated. Eventually he left his teacher and went to live alone in a little hut. It had once belonged to a national teacher and it was now empty. Xiangyan was weeding there — you can imagine imagine how many weeds must have grown up. As he was scything away at the grasses, he knocked over a bamboo pole and it hit a tile and made a tock, and suddenly he was awakened.

The poem wrote from that moment begins, “One strike and I forgot all I knew.” So all of the that knowledge just fell away and there was nothing between him and this sound.

Water Drips from the Eaves

Here’s another koan. I'll give you a little bit longer version of this one. It is is about a teacher named Shexian Guixing.

A monk asked Shexian, “Can you explain to me about Zhaozhou’s ‘cypress tree in the garden?’” What is the meaning of Zhaozhou’s cypress tree in the garden? When he asked the question, the monk was referring to another koan, a very famous koan, where the great teacher Zhaozhou was asked, “What is the meaning of Bodhidarma’s coming from the West?” This is a very common question which means, roughly, what are we doing here? What's the point of all this? What's this about? In other words it's like, Help me! Help me out here teacher!

When Zhaozhou heard this question, What is the meaning of Bodhidarma’s coming from the West?, he said, “The cypress tree in the garden.” Just like I could say, “The cactus in the zendo.” So, when this monk asked Shexian, what is the meaning of Zhaozhou’s cypress tree in the garden, he's in some sense asking this same question: What are we doing here? What does this mean? What what is reality? What is life? Why am I here? Help!

Shexian said to him, “I could tell you, but would you believe me?” The monk said, “Oh great teacher of course I would believe any words that you had to say to me!” The eye roll that the teacher gave was not in the koan but I can imagine it. What Shexian does is ask the monk, “Can you hear the sound of the rain dripping from the eaves?” The monk listens a little while and then he says, “Oh!” I love that little “Oh!” I don't know if there are any other “Ohs!” like that in these koan stories.

The monk’s poem of awakening was:

Water drips from the eaves,

So clearly,

Splitting open the universe,

Here the mind is extinguished.It’s something of the same thing as the other koan. No more, What is this? What is that? Who is this? Who is that? There is the sound, and the monk, but there is no longer the sound and the monk separately. There is the monk-sound, there's the monk-rain, monk-water, monk-eaves, monk-bamboo, monk-tile.

Pauline Oliveros

Pauline Oliveros was a composer who lived from 1932 to 2016, so she didn't die that long ago. She's best known for a practice that she developed called Deep Listening, which she once described as a practice of listening to everything, under all circumstances. in every way possible, at all times. Which is, of course, slightly impossible, but so are many of our vows. I think, for her, it was a vow not unlike a bodhisattva vow.

This kind of listening started when she was a child. [honking sound from the street] I'm listening to the beautiful car horn sound right now in her honor. When she was a child, she lived in Texas. It was the 1930s. There weren't so many cars and pavements and car horns and so the sounds that she listened to were the sounds of insects and frogs and wind in the trees and in the grasses. She described them as these “beautiful canopies of sound” that she fell in love with.

She also had a radio in her house when she was that age. Those kinds of radios needed to be hand tuned to the stations, and in between the stations were strange statics and tones and warbles, and she loved those as much as she loved what was intended to be listened to.

When she was nine she was given an accordion and that became her instrument. She's a well-known composer whose instrument is the accordion — I don't think there are very many of those. She played the accordion throughout her life. You can see its influence on her thinking so if you just kind of keep the accordion in the back of your mind.

When she was a young woman she was given a tape recorder. She said that the first thing she did is open the window and put the tape recorder out there. There was something she had intended to record — she doesn't really say what — but when she played the tape back she heard sounds that she hadn't expected, sounds she hadn't known were there. This is when she made the vow to listen to everything.

Sonic Meditations

She was also a pioneer of electronic music. She was part of some of the very earliest experimental electronic music labs. She invented instruments, she invented methods, she played with ensembles, she did many collaborations. At some point in the 1960s her heart became heavy with the political situations that were happening, and she decided to retreat for awhile. She retreated basically into a single note — for almost a year, she sang and played on her accordion only one note, the note of A.

From that experience, which she described as calming and as healing, she began to work with a small group of women in a feminist circle. They did breath, body, and sounding work. They began to make sounds together and these turned into something that she called Sonic Meditations. There's a book of Sonic Meditations that you can easily find online and download if you're curious to know what they're like. I'm just going to read you one of them. This group that she worked with weren't musicians per se — they weren't reading from scores — instead they were working together to listen and make sounds in a simultaneous way. The Sonic meditations are expressed as written instructions. Anyone could try them out.

Teach Yourself to Fly

This one, which is the first or central one, is called “Teach Yourself to Fly.”

Teach Yourself to Fly

Any number of persons sit in a circle facing the center. Illuminate the space with dim blue light. Begin by simply observing your own breathing. Always be an observer. Gradually allow your breath to become audible. Then gradually introduce your voice. Allow your vocal cords to vibrate in any mode which occurs naturally allow the intensity to increase very slowly continue as long as possible naturally and until all others are quiet, always observing your own breath cycle.

So that's the kind of practice that she was developing and it naturally turned into the practice of Deep Listening. Deep Listening is a vocal practice or sound practice as much as it is a taking in of sound, even though I think of it typically as about listening.

Deep Listening developed enough that she trained people in it. It took about three years of training to become a certified deep listening guide, which unfortunately I am not. But they're starting up the training again now. There's a Deep Listening Institute in her honor at Rensselear Polytechnic where she taught near the end of her life.

I wanted us to try out the listening part of of Deep Listening. We’re going to have an experiment in a moment and actually listen. If you're online. you listen to whatever space you're actually in of course, and if you're listening to this a month from now, again, you'll listen wherever you are.

Pauline Oliveros made a distinction between hearing and listening. For her, hearing was the passive phenomenon of sound waves connecting with your nervous system. It just happened all the time, but listening was something that was active, something that you did with your attention and awareness and your your full self. It included not just the literal sound waves. but but something larger.

She also distinguished between attention and awareness. For her, awareness was global, with no specific boundary. It had a center, which is yourself, but no end. It just went out as far as you could imagine. With attention or focus you could pick out particular sounds in the environment and bring them bring them closer to you and learn something about them — notice them in particular.

Deep Listening is a practice of balancing this global and focused kind of awareness.

I want to actually try it, and I'm going to set my timer for 3 minutes. This is a long silence for a talk, but I feel like I'm speaking to a group of people who are good at sitting quietly. I also feel that it takes a while to tune into to the subtle sounds around you. There are some obvious sounds, but there are subtle sounds as well, and it takes a while. It’s a bit like letting your eyes adjust to the dark if you're an astronomer.

So we’ll sit here for three minutes.

[Three minutes pass.]

Did you hear the car horn? Did you hear the air filters? Did you hear a distant siren? Did you hear a voice? Did you hear the sound of your own breath? Can you hear the sound of the rain dripping from the eaves?

Horse Sings from Cloud

I want to close with a poem of Pauline Oliveros.

It's really about the breath. For her the breath is very fundamental — it’s right in between listening and making sound. It's that doorway.

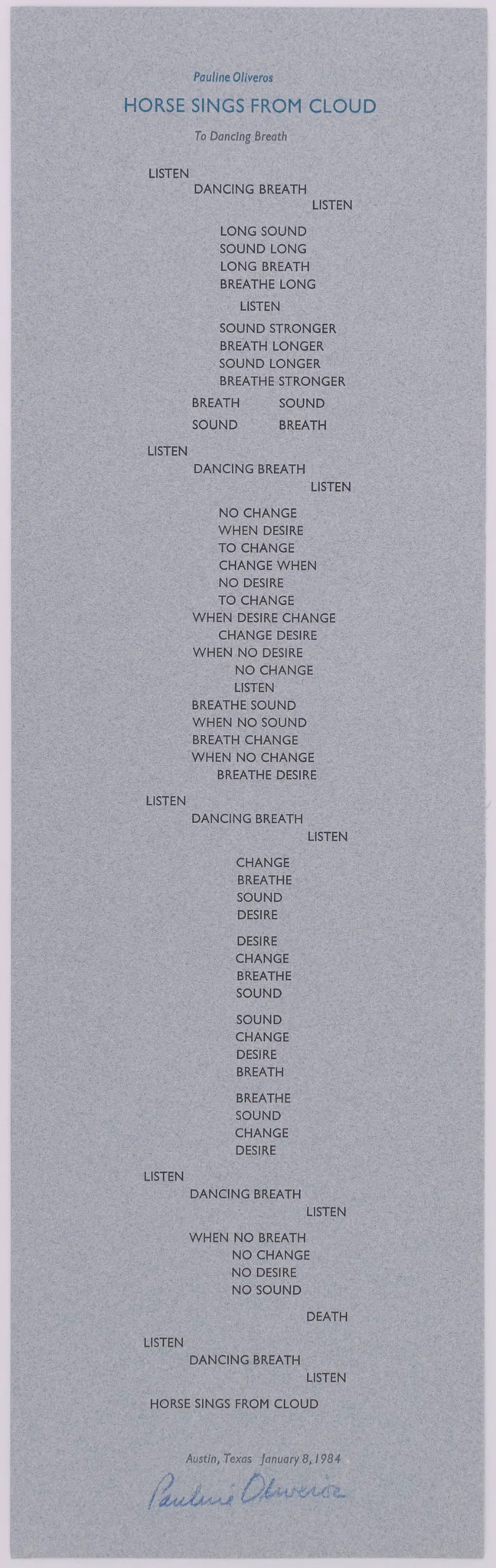

This is a poem of hers from 1984. It's called Horse Sings from Cloud and it's dedicated to Dancing Breath:

Pauline Oliveros

A broadside of Pauline Oliveros’s poem, “Horse Sings From Cloud,” is published by Black Mesa Press and available from Woodland Pattern Book Center.

Pauline Oliveros has written a number of books including Software for People and Deep Listening: A Composer’s Sound Practice. A new book, Quantum Listening, is available from Ignota.

Pauline Oliveros speaking on “The Difference Between Hearing and Listening.”

Zen Stories of Listening and Hearing

Zen’s Chinese Heritage: The Masters and Their Teachings by Andy Ferguson is available from Wisdom Publications. You can also find a PDF online here.

Further adventures and new ways of seeing can be found in my book, The Uses of Art.

Artist Sal Randolph’s THE USES OF ART is a memoir of transformative encounters with works of art, inviting readers into new methods of looking that are both liberating and emboldening.

Dazzlingly original, ferociously intelligent.

— Michael Cunningham

A joyful, dazzling treasure-box of a book.

— Bonnie Friedman

Here’s a guide, to waking up, over and over again.

— Roshi Pat Enkyo O’Hara

I really appreciated hearing you present in the video. Your first koan spoke to me strongly. It touches what I'm doing on Substack. After years of teaching and scholarly publishing (like your scholarly monk), I'm giving myself liberty to write first-person scenes with immediacy, among other things. There is satisfaction in the bamboo-strike of short essays drawn from life. And then one reconsiders how to talk or write about literature, after hearing those strikes.

Was it intentional to post this exactly on the anniversary day of Oliveros' death? She must have had some sense of humor, if those car horns are any indication. :-)

Thank you for this beautiful post 🤍 I’m going to be exploring further... the Sonic Meditations, Pauline Oliveros ...and the poem ´Horse Sings from Cloud’ dedicated to Dancing Breath ! - so alive and exciting - it gives me tingles, honestly. I find your substack such a joy 🙏✨