Dear Friends,

I’ve had some of my most intimate art experiences with still life paintings. Still lifes make attention to the world visible, in a manner I now associate with the practice of Zen. They remind us that every object in our surround is vibrantly present, if only we look.

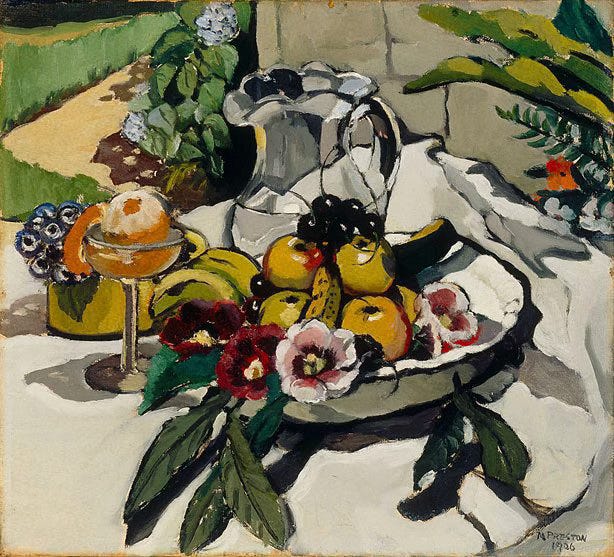

A few year s ago I had an exhibition in Australia, in the town of Toowoomba near Brisbane. When the show was over I spent some days in Sydney, just wandering the city, drinking lots of coffee, and seeing art. I went again and again to the Gallery of New South Wales, where I encountered the work of many Australian artists, including the painter Margaret Preston.

The peculiar intensity of her work struck me deeply and I began a lengthy research project related to her life and practice. Preston was born in 1875, studied painting as a girl in Australia and then traveled to France to continue her education. On her return, she became known for her still lifes, especially her paintings of flowers.

This week’s Ways of Seeing springs from the way in which we connect with ordinary objects, and takes inspiration from Margaret Preston’s work.

To me, her images speak more vividly than words, so I encourage you to spend some time just looking at them.

— Sal

Margaret Preston Still Lifes

Notes on Still Life from The Uses of Art

Still life—a painting whose determining quality is the unmovingness of its subject. The gaze shifts, but what is looked at remains silent. Nothing happens.

If I look at that cup long enough, in some sense do I become it? Do I feel myself growing hollow? Its objectness carries me deeper into subjectivity. The more I look, the more the cup begins to mean. Soon it is the universe waiting to be filled with itself. It is everything.

What does it mean to paint an object? To sit with it and watch nothing move. By looking at it, you submit yourself to its gaze—it studies you.

…

I’ve been hyped up for days, buzzing, unable to settle. I go from room to room in the house, book to book, task to task. Nothing is more difficult than sitting to complete something. Then I return here, to this task, to think about the world of objects. I walk my mind through a hall of objects, and return, once again, to my favorites: a table, a piece of fruit, a tool, a bowl, a lamp, a stone. I like to run even the words of them in my mind. And slowly, doing this, I begin to settle again, finding a kind of solace here among the nouns, in the realm of the actual, the complete, the self-contained. Bowl, fruit, table. Bowl, fruit. Bowl. A stillness.

“There must be objects,” Wittgenstein says, “if the world is to have an unalterable form.”

The still life has always seemed to me an essentially religious subject in its quality of long contemplation, in its humility. Among the ‘great’ genres—icon, landscape, figure, history—it may seem modest. We often think of the artist in his or her studio, arranging and rearranging flowers or pieces of fruit. There is something almost funny in the image, something domestic, antiheroic.

“If the forms of still life were precarious, experimental, Icarus-like,” says critic Norman Bryson, “they might command attention and engage curiosity, but their point is that they can be taken entirely for granted.”

…

Still life—I always feel the echo of the variant reading, that life persists, that we are still here. Stubborn life.

Exercise: Still Life

Home

Choose an object from your ordinary environment. Place it on a table. If you like, offer it some companions and enjoy the act of arranging.

Begin by closing your eyes and sitting quietly in the darkness behind your eyelids. Open your eyes and offer your gaze and your attention to what is before you. If you start to feel distracted, close your eyes again for a time. Alternate seeing and not-seeing for ten to twenty minutes.

Gallery or Museum

Find a still life painting. If one is not available, take any image and look at it as if it was a still life.

Use the exercise above: begin with your eyes closed, and when you’re ready, pop them open to see the image. When your attention wanders, take that as an invitation to rest and close your eyes again. Alternate looking and not-looking for as long as you can.

As with all of these “Ways of Seeing,” the initiating impulse is to expand our possibilities for engaging with works of art and deepening attention to everything around us. These exercises are perfect for time spent in museums, galleries, and studios. You can also bring them into the rest of your life and experiment with streets, libraries, parties, landscapes. Try them as writing or art-making prompts.

These practices work best if you give them some time.

As ever, interpret these instructions freely and intuitively. Make them your own.

Share your results and reflections in the comments. I’d love to hear from you.

Margaret Preston

Margaret Preston painted this portrait in 1930 at the request of the Trustees of the Art Gallery of New South Wales. She confessed she was thrilled to receive the commission to paint what was, for her, an untested subject. As she later pointed out, '… my self-portrait is completed, but I am a flower painter – I am not a flower'. In a work as carefully designed and as uncompromising as the artist's still-lifes, Preston identifies and separates the essentials of her art: her brush and palette and a pot of wildflowers, a favourite subject, on the sill behind her. — Art Gallery of New South Wales

On Margaret Preston from the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

On Margaret Preston from the National Gallery of Australia.

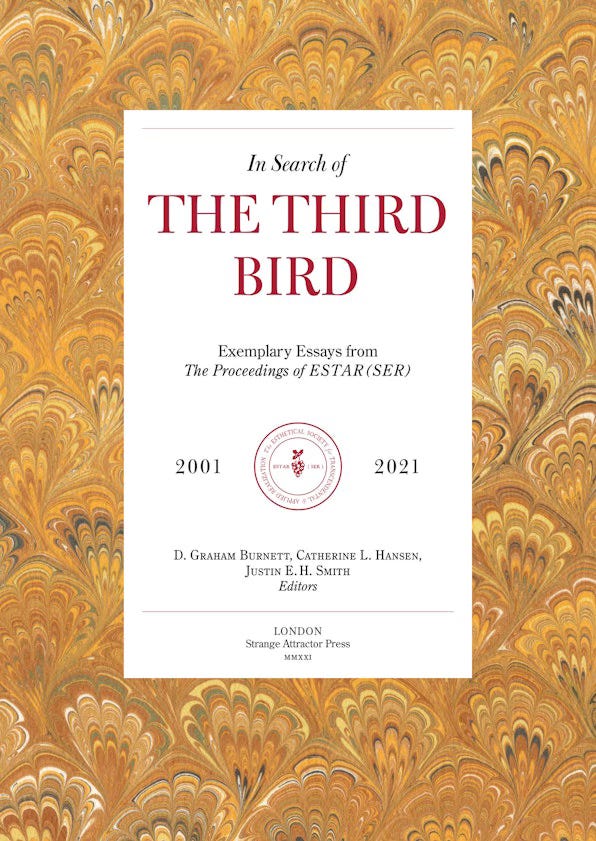

In Search of the Third Bird

I contributed to an essay on Margaret Preston which can be found in In Search of the Third Bird published by Strange Attractor and distributed through MIT Press.

Further adventures and new ways of seeing can be found in my book, The Uses of Art.

Artist Sal Randolph’s THE USES OF ART is a memoir of transformative encounters with works of art, inviting readers into new methods of looking that are both liberating and emboldening.

Dazzlingly original, ferociously intelligent.

— Michael Cunningham

A joyful, dazzling treasure-box of a book.

— Bonnie Friedman

Here’s a guide, to waking up, over and over again.

— Roshi Pat Enkyo O’Hara

I love that, Taishin. Dogen was much on my mind during the writing of the book and Watts always is as well), but as it happens those thoughts on still life were written way before I came to Zen. Zen before Zen.

As I read some of the Notes, I was reminded of Dogen’s description of awakening: Letting myriad dharmas come forward to realize you.

Then, I was reminded of Watts’s observation that we are an aperture through which the universe experiences itself.

Thank you for the post.