Dear Friends,

In New York, where I live, autumn has taken hold. Leaves are whirling in the street. Rainy nights, chill mornings, bright moon in the black sky. The sense of change, of the year turning, has made me wonder what it would be like to look at works of art through a seasonal lens. Can we see works of art as having seasons? Can we become sensitive to those evocations? What is seasonal attention?

For those who have joined us recently, welcome! “Ways of Seeing” is a series of inspirations and practical exercises for deepening attention and engaging with art.

— Sal

P.S. I updated this post to add a special bonus at the end—enjoy.

Seasonal Feeling

This week we take inspiration from the seasonal feeling (kisetsu) expressed in Japanese haiku.

Autumn, in Japanese poetry, is a time of rains, of big moons, of the cries of migrating birds and of lengthening nights. There is often a mood of loneliness or parting. Cold air brings vivid skies and the knowledge that winter is not far.

One of my favorite haiku vividly evokes this flavor:

I go,

You stay;

Two autumns.

Yosa Buson (as translated by Robert Hass)Traditionally, haiku rely on seasonal words, called kigo. Using one of these words evokes not only the season but also makes a link to a vast number of other poems springing from the same word—you could think of this as a poetic form of hypertext.

Kigo are gathered into saijiki, thick books which are simultaneously dictionaries, almanacs, and anthologies. They offer not only lists of seasonal words, but many examples of haiku from the great poets. No Japanese writer of haiku would be without one. Unfortunately, traditional saijiki have yet to be translated and published in English.

While there aren’t full sajiki, there are a number of resources available online, including this inspiring list of 500 Essential Japanese Season Words.

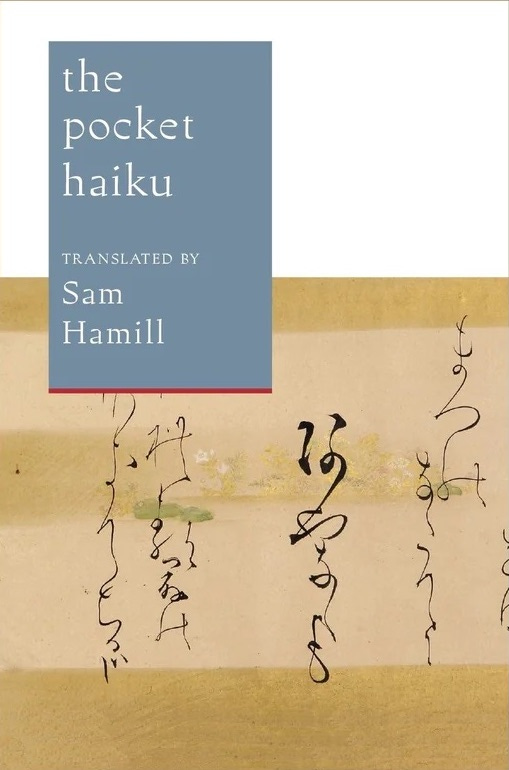

Here are a few more haiku for the season we are in, gathered from Sam Hamill’s Sound of Water (now reissued as The Pocket Haiku).

Matsuo Basho A solitary crow on a bare branch— autumn evening — Autumnal full moon, the tides slosh and foam coming in — Seas slowly darken and the wild duck’s plaintive cry grows faintly white — This bright harvest moon keeps me walking all night long around the little pond Yosa Buson With a runny nose sitting alone at the Go board, a long cold night — The late evening crow of deep autumn longing suddenly cries out — Utter aloneness— another great pleasure in autumn twilight — Brilliant moon, it is true that you too must pass in a hurry

Exercise: Seasonal Feeling

Works of art can embody seasons in many ways: through their colors, forms and images as well as their atmosphere or emotion. Looking for the season in a work of art can be an act of imagination or a leap of intuition—it doesn’t need to be literal.

This heightened awareness of seasons is a special form of attention which you can offer to a work of art, or indeed to any part of your life.

As with all of these “Ways of Seeing,” the initiating impulse is to expand our possibilities for engaging with works of art and deepening attention. These exercises are perfect for time spent in museums, galleries, and studios. You can also bring them into the rest of your life and experiment with streets, libraries, parties, landscapes. Try them as writing or art-making prompts.

These practices work best if you give them some time, at least twenty minutes or a half-hour. This is easier to do if you set a timer.

As always, interpret these instructions freely and intuitively

Experience: Place yourself in relation to a work of art. Ask the work what is your season? Notice any colors, forms, or images that give you a seasonal feeling—go beyond what is logical or literal. Let yourself enter the work and the season. Dwell there a while until you feel the season changing around you.

Response: Compose a short poem for the work of art, using whatever you have observed. This can be as small or easy as a list of three to five specific elements you noticed in the work. Ask yourself what feeling arose from these, and note it down as well. If you do this, it will already be a poem.

To go further, consider using the syllabic form of the haiku: three lines of five, seven, and five syllables respectively.

For something a bit longer consider a tanka: five lines, with five, seven, five, seven, and five syllables.

There is no need to be traditional unless you want to, but if you want a more in-depth guide to writing haiku, try this one.

Bonus!

Here’s another wonderful introduction to writing haiku from the poetry-comic artist Jason McBride at

. Open up your sense of form with his playful approach.Share your results and reflections in the comments. I’d love to hear from you.

More

Sam Hamill’s The Pocket Haiku is available from Shambhala Publications.

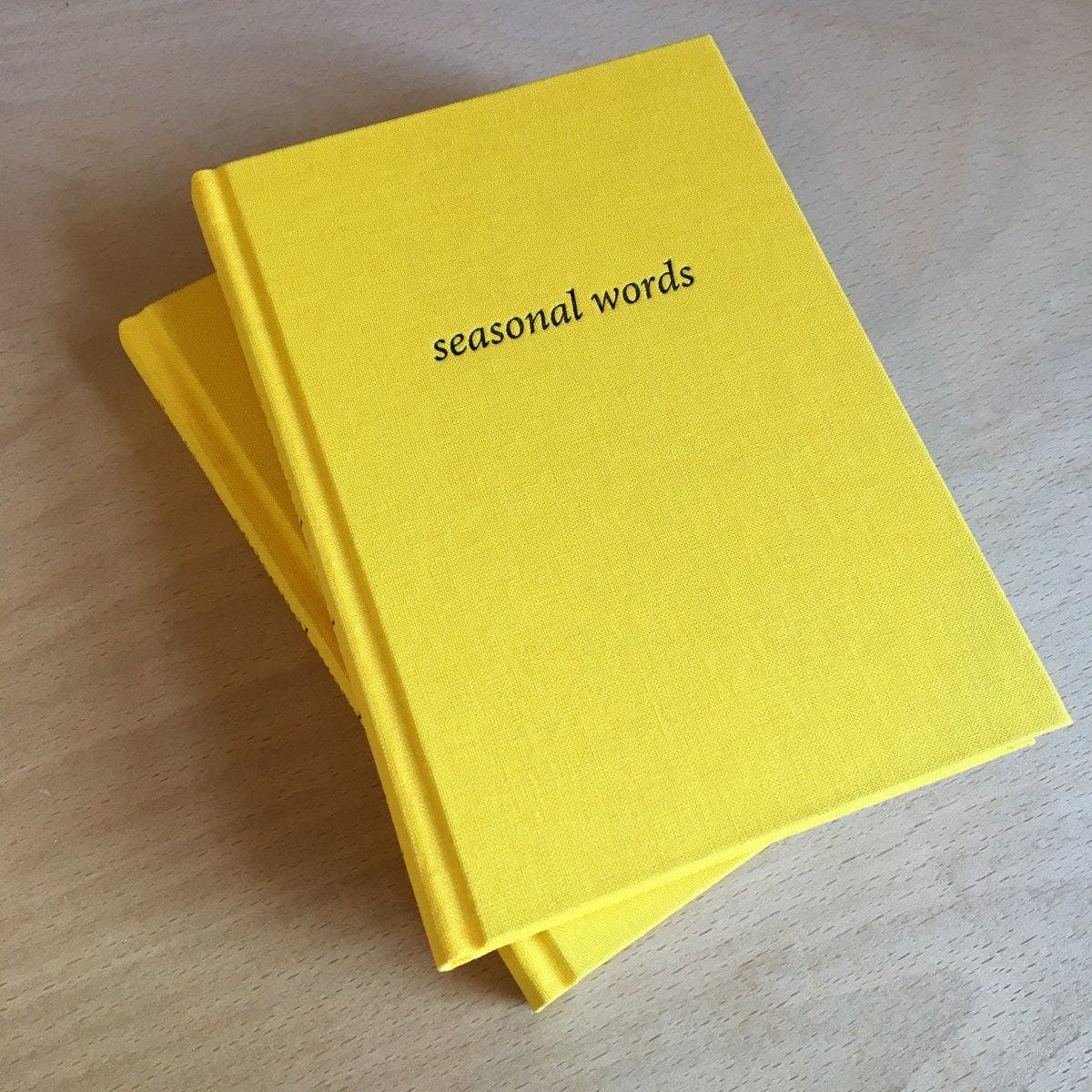

For further inspiration, consider this beautiful book, Seasonal Words, translations of fall and winter haiku by Harry Gilonis, from Coracle Press in Ireland (one of my favorite small presses). It’s not quite a saijiki, but it might inspire one. Meanwhile, it glows on my bookshelf.

The title Ways of Seeing is an homage to the continuing inspiration of the BBC TV series and book by John Berger.

Further adventures and new ways of seeing can be found in my book, The Uses of Art.

Artist Sal Randolph’s THE USES OF ART is a memoir of transformative encounters with works of art, inviting readers into new methods of looking that are both liberating and emboldening.

Dazzlingly original, ferociously intelligent.

— Michael Cunningham

A joyful, dazzling treasure-box of a book.

— Bonnie Friedman

Here’s a guide, to waking up, over and over again.

— Roshi Pat Enkyo O’Hara

I learned recently about seasonal words. This was a great read, thank you also for the link to the seasonal words!

While reading your post,

I feel autumn’s cool leaves, here.

Appreciation!