Dear Friends

I’m thinking in paragraphs these days, so much so that I’ve become fascinated by the history of the paragraph, and of its typographic mark, the pilcrow (¶).

I’m asking myself, what is the unit of thought? Of experience? What is the right size for a small piece of writing that is not a fragment but a whole thing. How much can happen in this small space?

Here are three recent paragraphs from the unnameable project I’ve been working on.

— Sal

¶

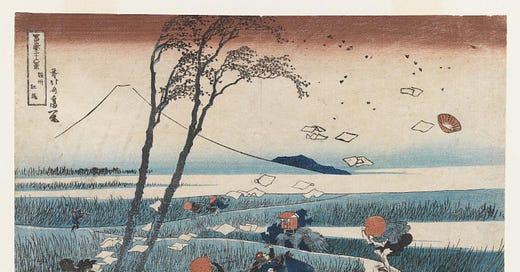

Snow falling hard and fast, like rain without becoming rain. The streets and sidewalks are wet and sloggy. People are taking pictures of the sky, but there’s nothing to see: white on white. Later, we look back at what was almost visible at the time. Some phenomena change things without themselves being perceptible. There’s advice I give others which I ought to be applying to myself. The advice comes from experiences which disappear into the self, as if dissolving, and then are only made apparent when offered. What I mean is, there are parts of the self we can only see when we send them out into the world in some way. A flock of umbrellas goes by and I think of a Hokusai print and the Jeff Wall photograph that riffed on it. In truth I think of Jeff Wall first, before Hokusai. And as I write this I wonder whether either of them were ever real, or just ghosts of my imagination. Small figures, blown about by gales, tilting this way and that. There was a time when I was continually embarrassed, desperately uncertain about anything to do with my appearance. As if every gesture or accessory was itself a form of blushing. It lasted a year, maybe two. Now it’s almost the opposite and I move through my days as if can’t be seen by anyone.

¶

“Try not to think too much,” she says, which makes us happy as a parakeet’s wings overhead. I’m missing everything today: a book I used to carry everywhere, the way Twitter was once fun, a certain room in Iceland, and Iceland itself, and Iceland’s ice, meaning a glacier I visited as a tourist, but it’s not the glacier I miss — its gorgeousness — but the sense of motion. My therapist used to be alarmed at the way I identified with tourists instead of residents, even though I lived in the city and was born in the city. Maybe it’s just about letting something go every day, including the sound of your own voice. Like everyone else, I went to Iceland to write, to be as far away from myself as possible in order to be close to myself. Just now I’m wondering what my good friend wishes I were telling you. I know she has opinions. Pinion feathers. Wings. A taste in my mouth. The sound of an artificial wind. I was listening, and that’s what I heard you say.

¶

Any object can seem reluctant, stubborn. A cup, say, which resists all of your thoughts. We’re used to the way thoughts become gestures invisibly — almost effortlessly the hands move. It’s not magic, it’s just desire. The cup, or a door, stops the hand in its motion. When my hand touches the cup, the cup is filled with sadness, and it is sadness I sip at during the long afternoons. Sadness causes my thighs to ache and my ankle to twinge. It is the cup that sends me to the door. When my hand touches the door, I revise everything I am saying. Does it matter if I step into the hallway and go down the stairs? The cup is still there, on the table where I put it, with an inch or two of lukewarm thought. What if these are the only characters in my story, a white ceramic cup sourced from an indifferent merchant and a metal door painted with a stripe inside and out. Why do we allow this? Aren’t there other ways to live? The cup has a mouth, and it is constantly telling stories. Once, long ago, there was a cup like this in the hands of a nun. Even nuns have to drink, you see. She used the cup to hold everything she knew, so she could refer to her knowledge by taking a sip now and then. She made a habit of it (ha ha). She was carrying on an argument by letters with a man who thought her church was a fraud. How could he possibly think she would agree? Each time she wrote back, she gave a little smile as she closed the envelope. She, too, had desires, of course. Or was the cup telling a story about its own desires? Did the cup remember everything it had held and everyone who had held it? More than that, could it remember the contents of all those other cups that shared its shape and function and the uncountable number of hands? The shape of the cup is itself the shape of desire and the shape of loss.

More

On Jeff Wall and Hokusai from the Tate Museum.

Jeff Wall talking about his work:

Upcoming Classes

Oracular Writing

A Generative Writing Workshop

with Kathe Izzo and Sal Randolph

March 16, 3-5 pm.

Online

Find new space in your writing and devotional practice during this two-hour workshop with poet-friends Kathe Izzo and Sal Randolph. We will use oracular techniques and forms of writerly divination to invoke our muses and invite the playful trance of the literary subconscious. We will write together under the auspices of generosity, pleasure and spontaneity. No preparation or previous experience is needed.

About Us

Kathe Izzo and Sal Randolph have been poet-friends and frequent collaborators since encountering each other in Provincetown in the ’90s. Their collective projects have included readings, exhibitions, performances, and workshops.

Kathe Izzo/The Love Artist is a conceptual artist & poet working in many mediums from social engagement to long form meme poetry & more, with her specialty being the intuitive space of the noosphere, the meta landscape where we all dream together. Of all the anthologies & journals she has been included in, her favorite is THE OUTLAW BIBLE OF AMERICAN POETRY (Thunder’s Mouth Press). Kathe’s substack: My Braniac Amor.

Sal Randolph is an artist and writer who lives in New York and works between language and action. She is the author of The Uses of Art, a memoir of transformative encounters with works of art, described by Michael Cunningham as “dazzlingly original, ferociously intelligent.” Her poems have been featured in BOMB, jubilat, Sound American, and elsewhere; her performance and social art works have appeared internationally at museums and in exhibitions including the Glasgow International, Ljubljana Biennial, Manifesta 4, and the São Paulo Biennial. She has taught at Princeton and Bennington College. Sal’s substack: The Uses of Art.

Oracular Writing

with Kathe Izzo and Sal Randolph

March 16, 3-5 pm ET

Online

A recording will be made available following the workshop.

$55

Zen and the Art of Attention

3 Mondays 7-9 pm starting March 4th

The Strother School of Radical Attention

138 S. Oxford Street, Brooklyn

Attention and distraction can seem like new problems—part of our distinctively contemporary life—yet there is a rich history of contemplative practice stretching back thousands of years and across continents. Almost all spiritual traditions include some form of quiet sitting and contemplation; these practices could be considered technologies of attention, part of our collective cultural heritage. Can they offer new ways of relating to the commercialized attention economy we live in today?

This course offers an introduction to one such tradition, Zen Buddhism, as seen through the enigmatic and poetic essays of the great thirteenth-century Zen teacher, Eihei Dogen. We will engage in close reading of three key essays, “Bendowa” (“On the Endeavor of the Way”), “Genjokoan” “Actualizing the Fundamental Point”) and “Uji” (“Time-Being”). The course will culminate in an Attention Lab which will include an opportunity to experience the practice of Zen meditation.

March 4th - March. 18th

Mondays, 7:00 - 9:00pm

Strother School of Radical Attention

138 S. Oxford Street, Brooklyn

The course will culminate in a free, public Attention Lab.

Cost: $200 (sliding scale from $160, some full tuition scholarships available).

Further adventures and new ways of seeing can be found in my book, The Uses of Art.

Artist Sal Randolph’s THE USES OF ART is a memoir of transformative encounters with works of art, inviting readers into new methods of looking that are both liberating and emboldening.

Dazzlingly original, ferociously intelligent.

— Michael Cunningham

A joyful, dazzling treasure-box of a book.

— Bonnie Friedman

Here’s a guide, to waking up, over and over again.

— Roshi Pat Enkyo O’Hara

Love the three paragraphs from the project that shall not be named!

I loved your paragraphs and the gusts of wind! Thank you for this, you are an inspiration.