Dear Friends,

Over the past couple of weeks I’ve had a startling set of encounters with the paintings of Dana Schutz. I didn’t expect to be changed by them, but I was.

Works of art have a reality that goes beyond the artist’s intentions and beyond the ideas of critics and art historians. Art only comes alive as you experience it. Even if the work itself is in a fixed form like a painting, the experience of it is constantly shifting. In a sense, a painting becomes a new painting every time someone looks at it — every painting is at once finite and infinite.

I’m sure I would see something different if I looked at Dana Schutz’s work at some other moment in my life. At this moment, I saw the monsters I needed to see.

— Sal

There Be Monsters

When I walked into Dana Schutz’s show, Jupiter’s Lottery, I had spent the morning reading a book called Ugly Feelings (by Sianne Ngai). I had been looking at the chapter on disgust, and following the trail of anthropologist Mary Douglas’s Purity and Danger which deals with the boundaries we make between clean and unclean. I had been also been reading Lauren Elkin’s new book, Art Monsters, about the way women artists are often read as excessive.

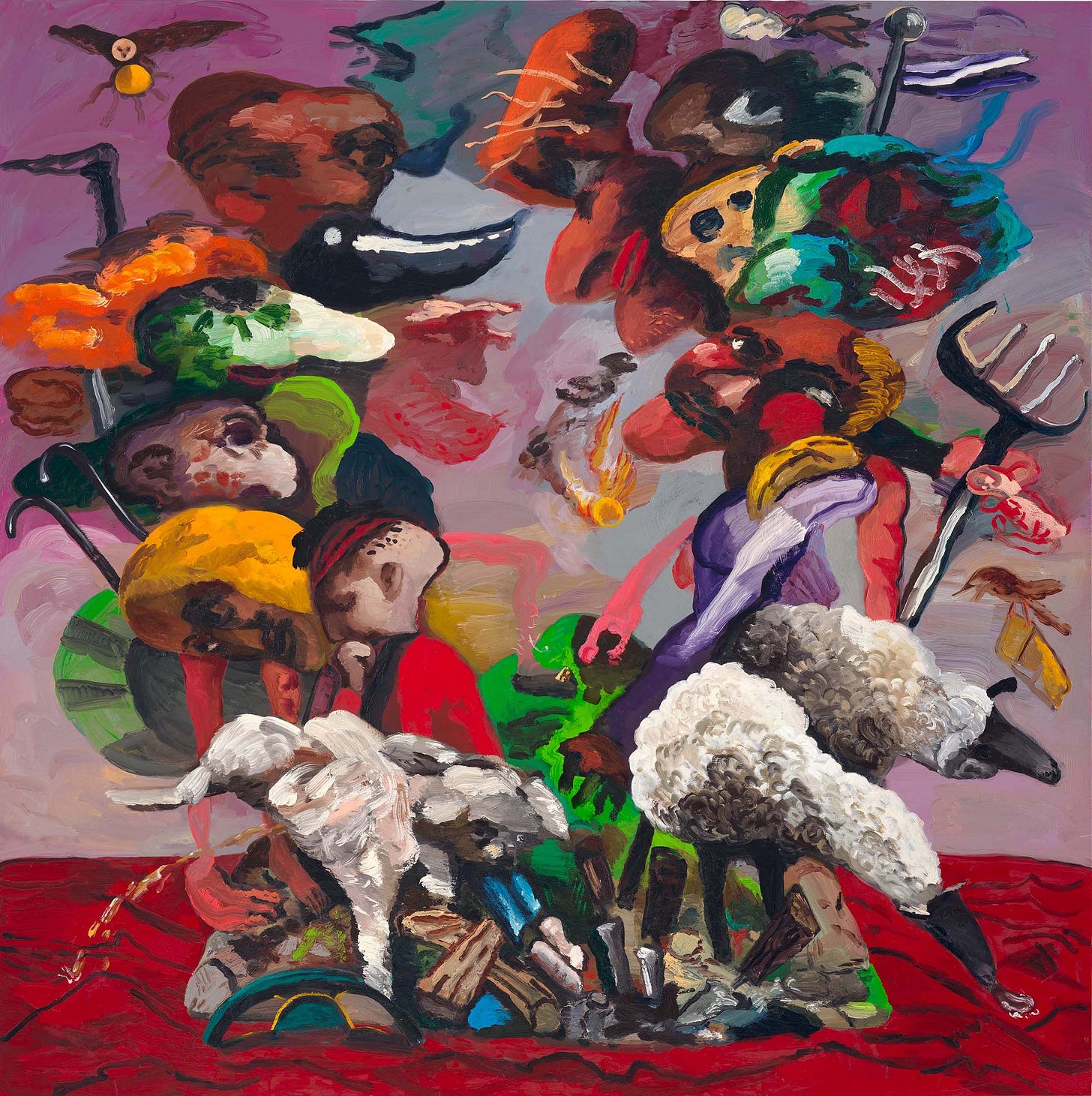

I came in the door and everything was monsters. The paintings seemed to deliberately court feelings of disgust. A dog lifts its leg and pees, a long curl of yellow fly paper collects flys from a swarm in the air. Underneath someone’s crotch a plate of raw meat lies on the floor. Heads are swollen and distorted. Limbs are elongated and do not always resolved into the familiar bipedal forms.

A monster is something that is too big. Any part of you that swells or grows can be a monster, a too-big, a toobig. We represent monsters by an enormity of the body — a gigantic form, a swollen feature or limb — but we know that the real monstrousness is an enormity of feeling, desire, purpose, intent.

The need to curtail (curtail oneself, curtail others) is part of living in a social world, but it does a violence to the self even as it protects communal life. People socialized female are taught to curtail more, and therefore suffer disproportionately. The same is true of anyone lower on a social hierarchy. The monster is a figure of the uncurtailed. The monster heals and inspires; the monster terrorizes and does violence. The monster rages across the landscape. The monster is unable to stay within boundaries.

Paint & Painting

Dana Schutz is a capital P painter, a painter who revels in paint itself. Photos of Schutz in her studio show every surface splattered and splotched. She engages in the romance and heroism of painting. Schutz herself looks quite ordinary: familiar, a friend. Cheerful under a barely controlled expanse of frizzy hair. How could these forms occupy her? Burst out of her?

Seeing Schutz’s work as tame internet images on a clean(ish) screen removes most of their force. It’s the paint itself that has become monstrous, that has exceeded what we can manage.

To see these works you have to see them up close; you have to see the actual paint. Paint itself — paint the material — contains the qualities that manifest in these paintings. Paint is intimate, like skin or a garment; it is a surface that is also a substance; it reveals and conceals simultaneously, it is wet in a state of becoming but over time it firms up into semi-permanence: from molten to frozen like lava or alive-dead like a zombie.

To see these paintings you also have to step back. These are story paintings, huge allegorical images, and their scale means that you often have to stand at the farthest corner of the room to make out what is happening. Even then, ambiguities remain.

Is it consolation or terror that the figures don’t seem to have proper boundaries, that there are bodies without parts and limbs without bodies? Too many heads, too many arms or legs. There is the feeling that if you could just see clearly some of the fear and tremblings would subside.

Among the paintings, I felt waves of existential unease. The feeling was sufficiently strong that I longed for language. I wanted to wash up against the shore of the press release and hear what someone had to say about all this, even if everything they said was wrong.

On subsequent visits, the paintings shift and shift. Sometimes the monsters seem more familiar, funnier, more tender, a kind of teasing. When the monsters don’t fully monster, I am disappointed. I miss them, maybe even long for them.

These paintings raise visceral questions. Why am I thrilled? Why do I want to be this excessive? Why am I also appalled or repelled? What does it mean to be a monster and why do we depict them by means of distortion?

Think of the monsters resting, sleeping in their monster-places, dreaming their monster-dreams. Think of monster-joy. What would it be like for a monster to eat one single fresh strawberry? What would it be like for a monster to walk in the woods, or swim, or play? Oh, monsters, are you cultivating your monster-gardens? Are you growing your monster-selves? The moral question of one’s own monstrousness: to grow it or wither it. It is a problem I don’t have an answer for. It is the river of impossible motion. It is the turmoil and turbulence. But just there, just a foot away, is the river that flows to the sea.

The exhibition Dana Schutz: Jupiter's Lottery is on view at David Zwirner Gallery in New York through December 16, 2023.

Afterword

Maybe this should be a foreword instead of an afterword. Certainly this story was also on my mind as I entered the gallery.

In 2017, during the Whitney Biennial, Dana Schutz was condemned for exhibiting the painting Open Casket which depicted the body of Emmet Till. Protesters called for the painting’s removal and destruction. Artist Parker Bright stood in front of the work, blocking would-be viewers and wearing a shirt that said BLACK DEATH SPECTACLE.

Open Casket remained on display at the Biennial with a new wall label and Schutz kept painting. A major retrospective of her work is currently on view at the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris. Nevertheless, it remains impossible to see her work without thinking of how painful that moment was for Black artists and viewers. In Art Monsters, Lauren Elkin comes to the conclusion that the painting should have been destroyed — yes to art monsters, no, or at best maybe, to Dana Schutz.

Back in 2017, I saw Open Casket in the show and I read everything I could about how people felt. For me, it was a situation of deep and complex learning.

During a recent conversation with Schutz, Hamza Walker remarked, “For all the controversies that we have surrounding photographs or surrounding paintings, at the end of the day these photographs and paintings expose things. They can expose our feeling. And they’re places where, if it’s to be worked out, what other place or better place than through the mechanism of culture, to have a discussion, no matter how heated? It ultimately adds to our level of consciousness and sensitivity, and to be able to reflect upon things.”

More Information

Dana Schutz at David Zwirner.

Aruna D’Souza on Dana Schutz and Parker Bright: “Who Speaks Freely? Art, Race, and Protest.”

A recent interview with Dana Schutz:

The interview with Hamza Walker can be found in a new monograph on Dana Schutz which is out from Phaidon.

For more on monsters and monstrousness, I recommend Lauren Elkin’s Art Monsters, published by FSG.

Further adventures and new ways of seeing can be found in my book, The Uses of Art.

Artist Sal Randolph’s THE USES OF ART is a memoir of transformative encounters with works of art, inviting readers into new methods of looking that are both liberating and emboldening.

Dazzlingly original, ferociously intelligent.

— Michael Cunningham

A joyful, dazzling treasure-box of a book.

— Bonnie Friedman

Here’s a guide, to waking up, over and over again.

— Roshi Pat Enkyo O’Hara

Phenomenal essay, Sal. You have such a gift for writing about art. I appreciate how you personalize it. Feels like visiting a show with a super knowledgeable friend. I’m glad you made the story about “Open Casket” an epilogue. If it had been first, I think I would’ve felt very differently about the rest of the piece.

"Among the paintings, I felt waves of existential unease. The feeling was sufficiently strong that I longed for language. I wanted to wash up against the shore of the press release and hear what someone had to say about all this, even if everything they said was wrong." .... This stands out so much to me. I am someone who always reads the words about a work of art before I look at the art, except when I consciously make the effort not to do that, and a lot of that has to do with issues of control and anxiety. GREAT ARTICLE.