Dear Friends,

I’ve been experimenting with fiction lately. Here are two very short, interconnected stories. I won’t say more now, but I’d love to chat in the comments.

— Sal

Bread Mother

The mother was impatient, even though she was dead, especially because she was dead. She fanned her deck of lives on the marble tabletop, asking me to pick one. I shook my head mutely. It wasn’t going to be like that. I tried to sit up straight. I got my hair out of my eyes. I chewed with my mouth closed. These were the rituals I used to make her fade a bit so I could read my book in peace.

Then the phone was ringing and it was the mother again. The phone is always the mother, it is always a request. In the book I was reading, the plot began to unravel, becoming smoke. The air was cold and dry — air-conditioned-air touching my cheek and perking my nipples uncomfortably. I held in a punishable sigh.

I had glimpsed the mother this morning in the back of my closet as I was looking for a lost garment. My eyes accidentally fell on the priority mail box that contained what remained of her. I had encountered the mother in the book I was reading, disguised as someone else’s mother. The mother had found her way into a conversation just an hour ago.

The mother, I found myself saying, had been a bad girl in a good family, secretly and briefly pregnant as a teen. Her girl gang broke into people’s houses for the pleasure of breaking and the pleasure of into. This, as we walked the dog through a pleasant autumn morning.

The mother inhabits a body exactly shaped like mine, walking in the exact way I walk, walking the dog on an autumn morning. When I lift my hand, her hand lifts. When I eat, she eats, whether she likes it or not. Living like that would make anyone cranky and imperious, but in the case of the mother, nothing needed to make her that way.

The phrase “the mother,” is borrowed. It’s the kind of thing you might find lying around the landscape, littering the city (but if you’re reading this, however unlikely, you know who you are, and thank you). Every person walking down the street is doubled, their outline blurred by what dwells in them. Doubled and redoubled. Troubled by the infinite regress.

Once, I ate a pancake that used as its rising agent a sourdough which had been alive a hundred-fifty years. During the Klondike gold rush, miners harbored the mother of sourdough under their armpits, keeping it warm as they traveled. Bread mother, mother of tea gone strange, mother of vinegar.

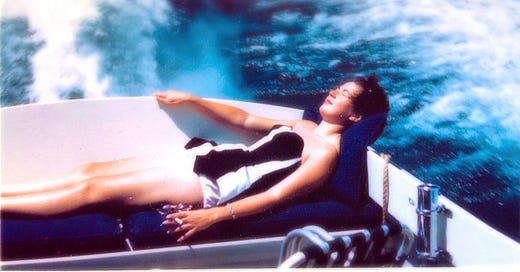

To bring peace to the mother I picture her in the moment of her greatest perfection, lying in the back of a speedboat in a black and white bathing suit, cherub-faced, eyes closed, cigarette in her outstretched hand. In that picture, I’m the one who is the ghost. I fill the outlines of her body as a shadow from the future. I taste the cigarette in her mouth and rest in the buzzing roar of the boat’s motor.

The pancakes were served with a compote of blueberries, the small ones we call “wild.”

Fox Mother

Again with the mother. Again with the again. The mother itself is the again.

I am lying on the couch but not her couch. Around me are portraits of apples, each apple peculiar in its own way. The phone rings and I don’t answer. It’s the old kind of phone, with a handset and a curling cord. The handset stays in the cradle, vibrating with sound.

Tell me a story, says the waiting air.

Once, there was a fox, a vixen, hungry in winter. She trotted the fields hunting for mice. Every place she put a foot was a place she had stepped before. It was dusk.

It was dusk?

Yes, it was dusk.

And then?

The vixen’s mouth wanted to have a sharp conversation with a mouse.

And your mouth?

Oh, that again. Did you know that foxes, when chased, run in great circles?

Is that what you think we are doing?

There is something about this that’s like a dream, I say.

In another timeline, I pick up the phone just to hear the dial tone. The tone itself is a memory of something that happened hundreds, maybe thousands of times. Somewhere, right now, there really is a fox in a field with a bloody mouth. Every hair on the fox is beautiful.

The mother liked furs and wasn’t afraid to wear a fox or a mink. She draped the evidence across her shoulders like a glamour.

Tell me a word, I say to her.

I’d love to hear your thoughts. How are you feeling about fiction these days?

Further adventures and new ways of seeing can be found in my book, The Uses of Art.

Artist Sal Randolph’s THE USES OF ART is a memoir of transformative encounters with works of art, inviting readers into new methods of looking that are both liberating and emboldening.

Dazzlingly original, ferociously intelligent.

— Michael Cunningham

A joyful, dazzling treasure-box of a book.

— Bonnie Friedman

Here’s a guide, to waking up, over and over again.

— Roshi Pat Enkyo O’Hara

You had me from “The mother was impatient, even though she was dead.” Really lovely being led by you to so many unexpected places!

Oh, my, Sal. This is mesmerizing. The rhythm held me in sway. I love the simultaneity of time here -- how the past is present and vice versa.

Some of my favorite lines in the first one: "I held in a punishable sigh." "Her girl gang broke into people’s houses for the pleasure of breaking and the pleasure of into."

And jolts of recognition! ". . . in the case of the mother, nothing needed to make her that way."

I was thinking as I read the second one, this is like a dream, and then it became self-aware! ha!

"Every hair on the fox is beautiful."

Gorgeous, Sal. Every hair.